A new 3D printing process eliminates the need for support structures and can one day print with unprecedented speed, researchers said.

June 8, 2022

3D printing may print 3D objects but the process itself, which involves layering of materials, is primarily a 2D affair. However, researchers have set out to change that with a new process that they said is a “true” 3D-printing experience, they said.

A team from Rowland Institute at Harvard University developed a new volumetric 3D-printing process that eliminates the need for support structures typically used to create complex 3D objects because the resin it creates is self-supporting, researchers said. The process also can one day allow this type of printing to be done with unprecedented speed, they said.

Typically a 3D-printing process lays down flat layers of resin that are exposed to laser light, which hardens them into plastic. This process is repeated with the material distributed bottom to top in layers to take a 3D shape. However, if the object is complex and involves, for example, an overhanging piece—think a plane wing—the printing process requires some kind of support structure so the object stays together.

The Harvard team aimed to eliminate this structural support and create a process that moves beyond linear layering into the true 3D realm, observed Daniel Congreve, an assistant professor at Stanford and former fellow at the Rowland Institute, where most of the research took place.

“What we were wondering is, could we actually print entire volumes without needing to do all these complicated steps?” he said in a press statement. “Our goal was to use simply a laser moving around to truly pattern in three dimensions and not be limited by this sort of layer-by-layer nature of things.”

Novel Approach to 3D Printing

To enable this new process, researchers had to make changes to not just the resin that they used in their process but also the type of light it was exposed to for hardening, they said.

Researchers added what’s called an up-conversion process to the resin, which is the liquid material that hardens into plastic in the process. This served to change the type of light to which it reacts in the process from red to blue, they said. Typically, the resin hardens in a flat and straight line along the path of the light that’s shined on it. In the process developed by the Rowland Institute team, researchers added chemicals to the resin using nano-capsules so that it only reacts to blue light at the focal point of the laser created by the up-conversion process, they said.

This change means that the beam, which is scanned in three dimensions, can print the resin without needing to be layered onto something, researchers said. The resulting resin has a greater viscosity than that of the traditional method, so it can stand support-free in an object once it’s printed, they said.

“We designed the resin, we designed the system so that the red light does nothing,” Congreve said in a press statement. “But that little dot of blue light triggers a chemical reaction that makes the resin harden and turn into plastic.”

In the process, then, the laser passes all the way through the system and only turns the resin into a polymer material at the little blue dot, he said. “We just scan that blue dot around in three dimensions and anywhere that blue dot hits it polymerizes and you get your 3D printing,” Congreve explained.

Proving the Process

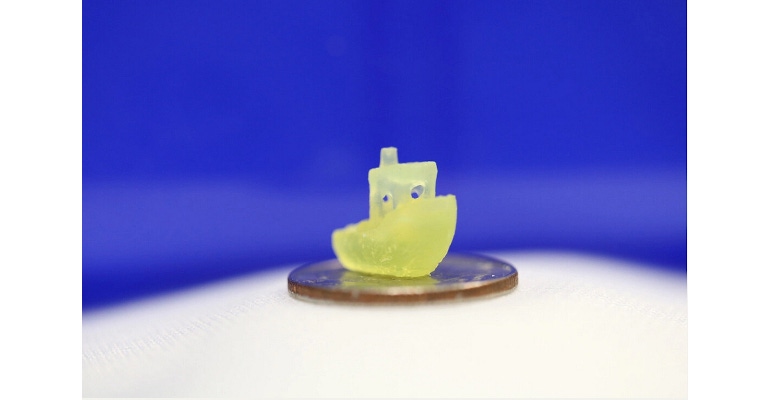

To prove that their process works, researchers scanned a number of objects, including a 3D Harvard logo, a Stanford logo, and a small boat. The last is a standard yet difficult test for 3D printers because of the boat’s small size and fine, overhanging details—such as portholes and open cabin spaces—that previously would have required support structures.

Researchers published a paper on their work in the journal Nature. While the process shows promise, researchers acknowledged it’s in its early stages of development and needs time before it lives up to its full potential.

“We’re really just starting to scratch the surface of what this new technique could do,” Congreve said in a press statement.

Researchers plan to continue to develop what they said is a “true” 3D-printing system so it can print even more quickly with finer detail, they said.

Ultimately, they think it can one day transform the future of 3D printing by not only eliminating the need for support structures but also for speeding up the process dramatically once it is completely optimized.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like