It seems that last month's SPE Thermoforming conference drew more than one person skeptical of the many claims surrounding the "green" revolution. Common sense, scientific data, and more reliable information could help processors sort fact from fiction.

October 19, 2010

It seems that last month's SPE Thermoforming conference drew more than one person skeptical of the many claims surrounding the "green" revolution. Common sense, scientific data, and more reliable information could help processors sort fact from fiction.

When Fabri-Kal Co., one of the largest thermoforming businesses in North America, specializing in food service and custom food packaging for the likes of General Mills and Kellogg, began looking at sustainable materials, it seemed to be a good fit. David McIntosh, senior engineer Materials & Development, noted that Fabri-Kal supports the technology to reduce U.S. dependence on imported oil and "it was a good fit with Fabri-Kal's ownership and management philosophy."

In 2002, as Fabri-Kal began working with the plant starch-based plastic PLA (polylactic acid), Dow was a material supplier to Fabri-Kal, and PLA's properties were well-suited to the cold-drink cups that Fabri-Kal produced. "PLA had similar shrink to PET and we were already making a line of PET cups, and we had the tooling for PET," explained McIntosh. "It looked like a drop-in technology. However, that's not the way it worked."

Some of the early lessons Fabri-Kal realized was the importance of temperature control and the difficulties of PET-to-PLA conversion for products. Other lessons included:

The older equipment Fabri-Kal had made it difficult to clean out the material to run PLA

PET doesn't melt at the same temperature as PLA

Equipment had poorer control at lower operating temperatures.

"There are so many ways in which PLA is different from PET, you have to be really careful," cautioned McIntosh. "There can be cross-contamination problems if there's a lack of communication between shifts, so plant-wide education is needed to train people in how to handle PLA in a PET plant. PLA requires more control and precision."

Today, Fabri-Kal processes PLA on a large scale, using high levels of regrind. McIntosh goes so far as to say that he believes the company has the "highest through-put PLA conversion line in the world."

'Green washing' a plague

That is all good. What McIntosh doesn't like is the amount of "green washing" going on as competitors and others strive to clam their products are sustainable. "At Fabri-Kal, we try to take the high road with respect to 'green' claims," he said. "There's a growing recognition of need for clear, meaningful and validated claims. The truth is gaining, partly driven by the FTC (U.S. Federal Trade Commission) and skeptical consumers, but there's no one single definition of sustainability."

|

Fabri-Kal focuses on the use of Life Cycle Inventory, published hard data that's available to all of its customers. "It's a tool that allows you to make objective comparisons between options," said McIntosh. "Data can be used (or abused) in different ways and there's no single metric for sustainability."

Greenware is Fabri-Kal's brand name for its line of drink cups and lids, crystal clear and made from Natureworks' Ingeo brand of PLA. Fabri-Kal's marketing approach for its products is based on hard data with "minimal spin," noted McIntosh. Greenware is marketed for its premium quality and appearance, its homegrown roots ('Made in the USA') from corn grown in Nebraska, and that it is made of a renewable resource that helps reduce the use of fossil fuel. There are also disposal options for the cups and lids. "We push our 'green virtues' very hard," McIntosh added, and noted that, "Marketing is a dangerous mix of fact and fiction. Carrying a paper cup versus a foam cup makes you feel better, but it's fiction that paper is better. We believe in selling the sizzle without trashing the truth."

McIntosh said that before requiring a product to be made from biopolymers, companies need to assess the options and define the needs and performance requirements. "Compare the options," he said. "Some customers just want 'fluff' so they can say they're green, and others want to see true sustainability."

Next, focus on direct, quantifiable benefits, costs and performance. Third, look at the end-of-life claims. "There are too many assumptions to make broad claims, and not all provide the solutions," said McIntosh. "Do a case-by-case assessment. There's no one material suited for all applications, so we must look at applications that use other materials."

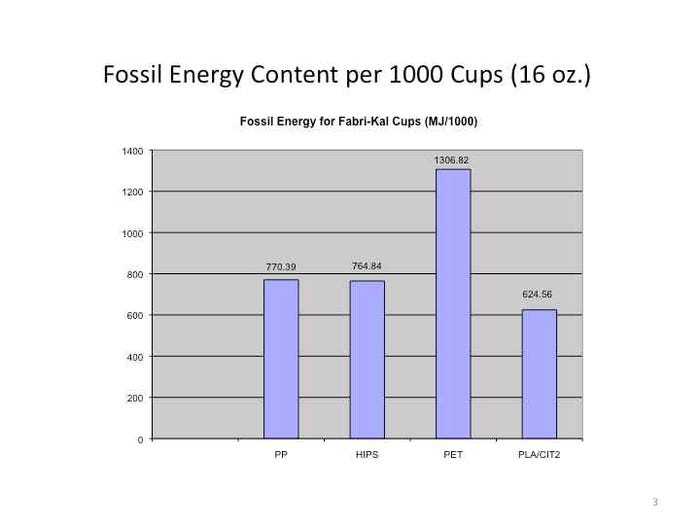

McIntosh believes that recycling is a viable answer; however, per capita the amount of waste is going down, even with population growth, and plastics recycling is "woefully low," he noted. He also noted that the fossil energy content (the amount of fossil fuel required to make 1000 cups) in PP and HIPS is almost comparable to PLA. [See graph]

So how does the industry dispel the myths and misconceptions that drive poor decision making and regulations? First, recognize the fact that there is no significant biodegradation or decomposition in landfills, and "it is not beneficial in any way," he stated. "Biodegradable is not an effective way to address the plastics issues. Biodegradability is stupid. There, I've said it! Biodegradability is not the Holy Grail of sustainable packaging."

Biodegradability is a "biological process" and "not compatible with an industrial process," said McIntosh. "Manmade plastics don't perform like plants in nature. Plastics won't degrade like leaves in a forest, which is a biological process. Plastics are created through an industrial process, which means there needs to be an industrial process to deal with the disposal." —Clare Goldsberry

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like