Sponsored By

News

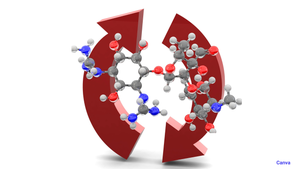

chemicals in beakers and pellets

Business

Encina Abandons Plans to Build $1.1 Billion Advanced Recycling PlantEncina Abandons Plans to Build $1.1 Billion Advanced Recycling Plant

The Houston-based company canceled the project in Township, PA, after the borough council voted unanimously to “strenuously and unequivocally oppose” its construction.

Sign up for the PlasticsToday NewsFeed newsletter.