Sponsored By

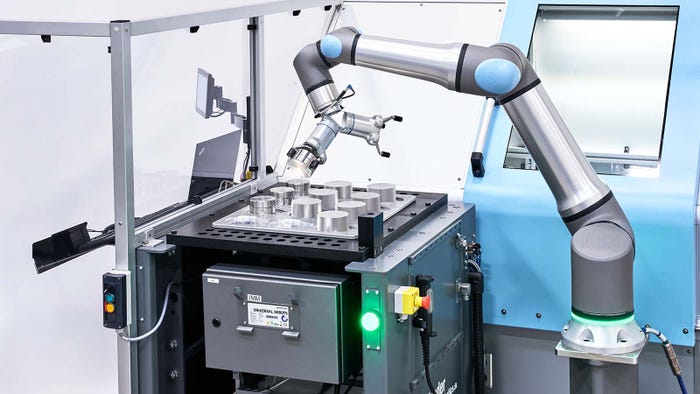

Automation

Michael Cicco, CEO of Fanuc America

Automation

Second NPE2024 Keynote Speaker AnnouncedSecond NPE2024 Keynote Speaker Announced

Fanuc America President and CEO Michael Cicco will address how the plastics industry is unlocking the power of automation and AI.

Sign up for the PlasticsToday NewsFeed newsletter.