The title of the film, which received the Oscar for best feature-length documentary, should have been “Chinese Factory.” The only American thing about the factory is its location near Dayton, OH.

February 18, 2020

This article was updated on Feb. 21 to clarify the sequence of events laid out in the first paragraph.

At this year's Academy Awards, Netflix’s American Factory, produced by Barack and Michelle Obama’s production company Higher Ground, won for best feature-length documentary. The title should have been “Chinese Factory,” because the only thing American about it is the factory’s location in the small town of Moraine, outside of Dayton, OH. While the documentary opens with the Dec. 23, 2008, closing of what was once a General Motors factory, we are never told the back story of that closing nor the role that Obama administration policies played after the president took office in January 2009, including further bailout negotiations, plant closings, and bargaining with the United Auto Workers (UAW).

Image from American Factory courtesy Netflix. |

An article in the Sept. 13, 2019, edition of the Wall Street Journal by Mike Turner noted that “despite being one of the top GM facilities for quality, efficiency and production in the country, it was shuttered.” The Moraine plant was a union factory, but many of the employees were non-union (workers cannot be forced to join a union as a condition for employment), leaving many of those workers transfered to other GM plants in the region in difficulty.

In 2014, Chinese businessman Cao Dewang bought the plant. He was known to workers as “Chairman Cao,” a monicker that echoes another chairman whose Great Leap Forward killed an estimated 45 million people in four years. (Some estimates put the total number of people killed throughout his rule to be upwards of 80 million.)

To the out-of-work citizens of Moraine, the arrival of Chairman Cao’s Fuyao Glass Inc. and the re-opening of the plant that would soon employ 2,000 people was greeted with open arms. Fuyao was seen as the “savior” of Moraine and its citizens.

At the plant’s grand opening, however, there were already signs of trouble ahead when Ohio Senator Sherrod Brown spoke to the crowd of Ohio’s “rich history of unions.” Immediately, Chairman Cao made Sen. Brown persona non grata on company property. “If union comes in, it will hurt our production,” commented Chairman Cao. “We’ll shut it down.”

The honeymoon was short-lived, as the employees began their indoctrination into the Chinese way of how manufacturing plants are run. Some 200 Chinese workers were sent from China to Ohio to provide training in plant operations. The Chinese groused that “Americans are slow to train” because they have “fat fingers.”

The working conditions were very hot, as one might expect in a factory where extremely high heat is needed to turn sand into glass. “Our American colleagues are very afraid of heat,” commented one Chinese worker. The American managers, supervisors and the president of the company tried to get Chairman Cao to make changes after OSHA found that the work areas were “too dense,” but nothing changed.

Americans also complained that the work was repetitive—“doing the same thing over and over again,” remarked one worker. “Do we have the stamina and will to continue?” He was doubtful. American employees of the new Fuyao plant, which supplied automotive glass to many vehicle makers in the U.S., were grateful for the jobs but, as one woman commented, “at GM I made $29 an hour.” Now she was earning half that.

Given that “output is first, speed is second,” injuries were commonplace. One injured man commented that he’d never been injured in all his 15 years working for GM, but now after two years at Fuyao, he incurred a severe cut injury.

It’s not that Fuyao doesn’t have a union in its Chinese plants—it has a “union” in the Communist Party headquarters at the plant. I’ve written in the past about how U.S. companies must give Chinese workers a certain amount of time off during the week to attend Communist Party meetings.

Productivity at the Moraine plant was low—not up to the standards of Fuyao’s Chinese plants—and there were myriad quality problems. The Fuyao plant was not reaching its goals. Chinese trainers complained that “American workers are not efficient and output is low,” said a trainer. “I can’t manage them. They threaten to get help from the union.”

Another manager commented that “American workers are lazy—it’s just their nature,” he said, adding that “every person can be changed; we have some diligent, motivated workers in China.”

I’m sure they do, and it probably doesn’t involve a motivational speaker! Obviously there is no work/life balance in the Chinese mindset.

To help provide a better look at the way Fuyao’s Chinese plants are run, a group of American managers was sent to China to see first-hand the Chinese way. If this section of the documentary doesn’t make you eternally grateful that you are an American working for an American company, nothing will.

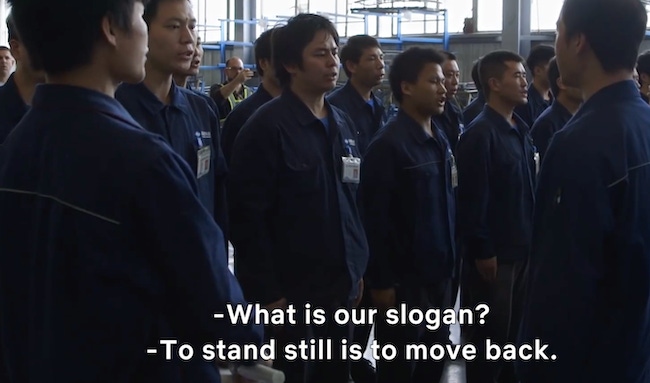

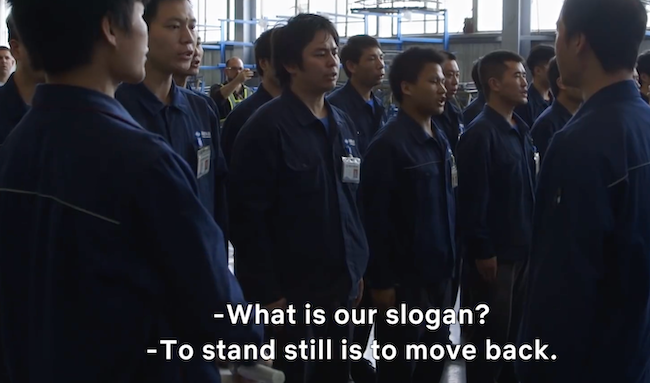

The Fuyao factory experience in China showed the American managers an almost militaristic way of managing. The 19 shift workers lined up shoulder-to-shoulder, in two rows, and counted off. The supervisor then confirmed that all 19 shift workers were present and accounted for. They then marched to their work stations.

Religious fervor for the state, first, and the company, second, was evident. At company meetings, “hymns” of praise are sung in deep gratitude for the good life the company, and Chairman Cao, has given them.

When the American managers returned, the documentary showed one manager trying to emulate the Chinese style. His shift workers were sort of lined up. They stood there looking rather glum—like, “why are we here?”—while he tried to give a bit of a pep talk. It obviously wasn’t working so he thanked them and dismissed them to start work.

Chinese workers in China commented that they work 12 hours a day, seven days a week with two days off a month. One worker said she goes home twice a year, and most of them don’t see their families much.

I’ve written about the Chinese dormitories where the workers live, sometimes eight to a small room on the premises of the factory. I’m reminded of the time I was visiting a large-sized custom injection molding company. I was in the conference room interviewing the president and owner of the company, when he pointed to a large framed photograph hanging on the wall of an elevated view of a large facility surrounded by a chain link fence topped with razor wire. “That’s our new China facility,” he boasted proudly to me.

I couldn’t help myself, and replied, “Is that fence with the razor wire there to keep the bad guys out or the workers in?”

Crickets.

We in the manufacturing sector know quite a lot about how the Chinese run their factories, and it ain’t pretty! I know personally several people who have worked for U.S. companies at their plants in China, attempting to do the reverse of what Chairman Cao tried to do at the Moraine facility. I’ve written about this many times over the years.

There was one really poignant moment in the documentary. During a large dinner celebration, the American managers were treated to entertainment by singers and dancers, both adults and children with happy, smiling faces and excited voices. At the end, the American managers got up on stage and did their rendition of YMCA by the Village People. The Chinese audience was greatly entertained, and they laughed and applauded.

The camera then shot a close-up of one of the American managers who seemed rather emotional. He got up and walked out into a hallway, commenting that he now sees something he’d not seen before. “We are all one,” he commented. “We are truly all one.” A young woman who started to walk past him turned and looked. “We are all one,” he repeated. “Yes, she replied, “all one company.”

This young Chinese woman had completely missed the American’s point. In many religious and spiritual traditions in the West we hear people promoting the idea that we are all one, great human family who all just want the same things: To be happy, to have meaningful work, to feed our families and enjoy life. In Buddhism, which it appeared that Chairman Cao practiced, there is a saying: “Everyone just wants to be happy and free from suffering.” In that respect, we are all one, something that the American manager suddenly realized, but the young Chinese woman didn’t.

I’d guess that the majority of U.S. manufacturing companies—small or large—want a safe work environment, because it’s the right thing to do, and pay their employees good wages, especially with the heavy competition for workers caused by extremely low unemployment.

As the former President of the Fuyao Glass factory acknowledged before he was fired, “We are not a union shop—we do things right by employees,” a reminder that it doesn’t take a union to create a good workplace and good wages.

If you thought this was going to be a movie showing how great a benefit unions are to the American manufacturing workplace, it was a fail in that regard. This isn’t a documentary about an American factory but a Chinese factory transplanted into America; it was about the attempts to meld two very different cultures, one of those a Communist culture that is very difficult for Americans to fathom.

At least the threat of union organization gave the Chinese management the impetus to clean up its act and realize that they are operating on American soil under American rules. While companies don’t have to be unionized to be safe and productive with well-paid workers, they really must “do the right thing.”

As one American woman worker noted toward the end of the documentary, “When we walk in the door of this plant, we’re in China.”

An attempt to unionize the Fuyao plant failed, primarily, as one worker pointed out, after the vote (60% against organizing), “They’re afraid of losing their jobs.”

Another worker commented, “they’re working their tails off and getting no pats on the back.”

To that the new Chinese president of the company (who replaced the fired American president) responded to complaints that Americans are hostile to the Chinese workers, and are super-confident: “You must take advantage of these American characteristics. Americans love being flattered to death—donkeys love being touched in the direction their hair grows.”

Are you insulted enough now?

In receiving the Oscar award, one of the directors of the film, Julia Reichert, gave a “shout out” to Karl Marx in her acceptance speech: “. . . people put on a uniform, punch a clock, trying to make their families have a better life. Working people have it harder and harder these days. We believe that things will get better when workers of the world unite.”

Does that quote sound familiar?

One other poignant moment at the end of the film is when Chairman Cao shows some introspection into his life. He lights incense at a Buddhist shrine, and wonders aloud if he is “a contributor or a sinner.” He is obviously an unhappy man, but concluded, as a good Communist might: “The point of living is to work.”

If you haven’t seen this documentary yet, please watch it on Netflix, and be very grateful for the life we have as Americans. And remember that throughout 2020.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like