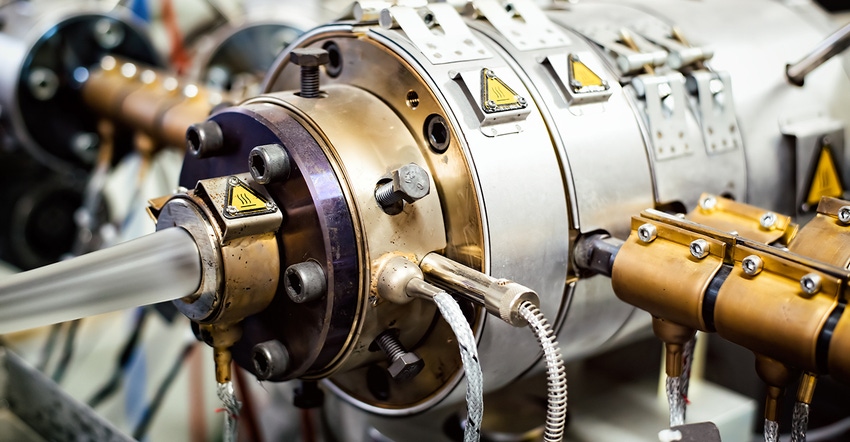

Purge compounds can speed up material changes and reduce the amount of scrap. They are especially useful between runs of incompatible materials on large extruders.

August 16, 2021

Around the year 1900, cars and trucks began to share the road with horses and people. They usually kept to the right (or left in the British Empire, Japan, and Sweden), but there were no lights at intersections to stop the flow in one direction and allow flow in the other. That led to towers with traffic cops to keep order, more or less.

The first stoplights in the US — some say the world — went up in Cleveland in 1912, but I remember the unique ones on New York’s 5th Avenue crowned by a likeness of Mercury, designed by Joseph H. Freedlander in 1929 and in use until 1964. Mercury is the Roman god of speed with winged feet — Hermes in Greek mythology. Mercury and bromine are the only elements that are liquid at room temperature. (Water is a compound, not an element.)

The 5th Avenue lights, like most of its predecessors, showed only red and green. With this two-light system, the red came on before the green went off. That way, if you saw red, you slowed down enough to stop in time at the intersection.

The yellow middle light was first used in Detroit around 1920, borrowed from the railroads. Garrett Morgan patented a four-way three-color system in 1923 and licensed it to General Electric, which made thousands of them.

What’s the connection to extrusion, other than the insulation of all the wiring? Stopping. This month’s column is about shutdown, stopping an extruder for a few minutes or more. The time matters, as the system starts to cool right away (but not always in the feed zone) and soon freezes all the plastic still in it, unless some heat is left on.

The following is adapted from my Plastics Extrusion Operating Manual, 24th Edition (2021). For more info on the manual or to order copies, or to talk about plastics as nontoxic and good for our environment and health, see my website, or call/e-mail me. The contact information is at the end of this article.

Material changes and shutdowns

Material changes and shutdowns should be planned as much as possible. For a material change, the new material must be ready (pre-dried, if needed) with a container available, if needed, for the hopper's existing contents.

You should follow light colors with dark, and easy-flow melts with more viscous ones, but this isn't always possible because of production scheduling and sales needs. Purge compounds can speed up material change and reduce the amount of scrap. They are especially useful between runs of incompatible materials on large extruders, as mixed scrap is low value and disassembly takes a long time.

Most purges are high-viscosity plastics, some with inorganic filler added for scouring, and often highly stabilized to avoid decomposition. Some purges have solvent action, and one type reacts chemically to depolymerize whatever is in the system.

In purging, temperature is important. Melt that resists purging when cool may get so soft when it’s hot that just changing temperature alone may work without using any purge at all. One such purge-less technique relies on cycling of screw speed.

Water as a purge? Steam may soften and blow out residues, but water alone is dangerous because steam may escape from the die or the hopper and scald anyone nearby. Water-saturated filled plastic may be safer.

Decisions, decisions

Shutdown requires a decision:

leave the screw full, half-full, or nearly full;

run the screw empty but leave head and die full;

completely disassemble and clean everything.

A screw may be left full to avoid decomposition at the breaker plate. In this case, cut off flow from the hopper with a slide plate and run a few seconds more to clear the first few flights. This will discourage bridging in the throat and sticking to the screw root in the feed zone during cooling and later startup. When the screw is finally stopped, keep barrel cooling on for a few more minutes.

To reduce contamination with decomposed plastic particles, run the screw at low rpm after the heaters are turned off, to get the melt temperature down and, thus, discourage decomposition. Some extruders put nitrogen into the barrel on shutdown to keep oxygen from the hot, reactive area at the end of the screw.

If the head is opened to change screens while leaving the die full and in place, be sure to clean the breaker plate and mating sealing surfaces carefully.

If the head and die are cleaned, do it fast, as a team. The plastic comes off easier when hot, and the first 10 to 15 minutes are critical to prevent degradation, especially with PVC. As soon as the motor stops, open the head bolts, get the screens and breaker plate out, and clean the sealing surfaces, while others clean the die at the same time.

Cleaning metal surfaces may require reheating in an oven or small-parts cleaner, such as a fluidized alumina bed, a pyrolysis oven, or an oil or salt bath.

When the die is not in use, protect its lips with a non-scratching, non-melting cover.

Should the screw come out, too? Some extruders never take the screw out and are content with occasional purges. Typically, these are large machines running commodity products, and downtime is costly. At the other extreme are UPVC extruders who take everything apart at (almost) every shutdown.

There may be a reason to pull the screw, such as material stuck on the screw root or to measure wear. In such cases, empty as much as possible, and follow with a purge, wax, or knitted copper mesh to make removal and replacement easier.

Use a screw pusher and hoist where needed; avoid sledgehammers or lift-truck forks that might damage equipment. Prepare to put the screw somewhere, pull it straight out, and with small ones don't pull its end up with a power hoist, as the screw might bend.

Screw cleaning as a half-way measure

Much of the screw can be cleaned while it is halfway out, still supported by the barrel and at a good working height. A strap wrench is useful. Some people use brass tools/brush and knitted copper mesh to avoid scratching, a good idea on internal die surfaces but not always important on screws, as it depends on the screw-surface material. There are also screw and die "soaps."

Sometimes a screw can go back without cleaning the barrel if it is hot enough for the melt to act as a lubricant. A hot barrel is also easier because of thermal expansion. However, unless a more stable shutdown purge is used, the old, degraded melt may lead to sprays of gels and "fisheyes" when production is resumed. To mechanically clean the barrel, put a long-shaft wire brush on an electric drill, or use mesh firmly wired or stapled to a broomstick.

Vacuum out anything loose. Don't use an air hose to blow material back down the barrel, because particles may end up in the screw seat and prevent full engagement there. Look into this area and keep it clean and lubricated.

For all lines, follow output per turn as a good way to "see" wear, even better than measurement alone, because if output per turn is not falling, wear may not matter.

Allan Griff is a veteran extrusion engineer, starting out in tech service for a major resin supplier, and working on his own now for many years as a consultant, expert witness in law cases, and especially as an educator via webinars and seminars, both public and in-house, and now in his new audiovisual version. He wrote Plastics Extrusion Technology, the first practical extrusion book in the United States, as well as the Plastics Extrusion Operating Manual, updated almost every year, and available in Spanish and French as well as English. Find out more on his website, www.griffex.com, or e-mail him at [email protected].

No live seminars planned in the near future, or maybe ever, as his virtual audiovisual seminar is even better than live, says Griff. No travel, no waiting for live dates, same PowerPoint slides but with audio explanations and a written guide. Watch at your own pace; group attendance is offered for a single price, including the right to ask questions and get thorough answers by e-mail. Call 301/758-7788 or e-mail [email protected] for more info.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like