In a recent study appropriately entitled 'Bioplastics', Cleveland-based industry market research firm The Freedonia Group explores the trends and developments in biopolymers from 2006 through 2016. The new study forecasts that U.S. demand for bioplastics will "climb at a 20% annual pace through 2016 to 550 million lb, valued at $680 million" and that "going forward, technical innovations that enhance the properties of bioplastics and lower their price will drive growth."

August 10, 2012

In a recent study appropriately entitled 'Bioplastics', Cleveland-based industry market research firm The Freedonia Group explores the trends and developments in biopolymers from 2006 through 2016. The new study forecasts that U.S. demand for bioplastics will "climb at a 20% annual pace through 2016 to 550 million lb, valued at $680 million" and that "going forward, technical innovations that enhance the properties of bioplastics and lower their price will drive growth."

The emergence of drop-ins—bioresins that are chemically identical to their conventional counterparts, such as bio-based polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polypropylene, and polyvinyl chloride (PVC)—are predicted to find rapid market acceptance, and will further spur the growth of this market.

Among these bio-based plastics, PET is projected to offer significant growth potential over the longer term, particularly as large corporations, especially those in the soft drink industry, are investing heavily in the development of this material. However, bio-based polyethylene, which entered the market in 2010, is expected to offer the best opportunities for growth through 2016, increasing rapidly from a small base. These exceptionally strong gains are predicated on the expansion of production capacity, which will reduce prices and enable this resin to compete more effectively with its petroleum-based counterpart.

Polylactic acid (PLA), which is used mainly in packaging, but also has a growing number of durable applications, is expected to remain the most extensively used resin in the bioplastics market. "Advances will be promoted by a widening composting network and greater processor familiarity, as well as ongoing efforts to diversify PLA feedstocks, as critics cite the food versus fuel debate and the energy- and pesticide-intensive nature of corn production as a key drawback of biopolymers."

As informative and thoroughly researched as this report may be, the current drought across the U.S. could dry up expansions in this area, at least temporarily. Although the sugar cane for bioplastics is usually grown on land in Brazil that has few alternative uses and certainly could not be used to grow grains, corn-derived feedstocks grown in the U.S. compete with feed resources.

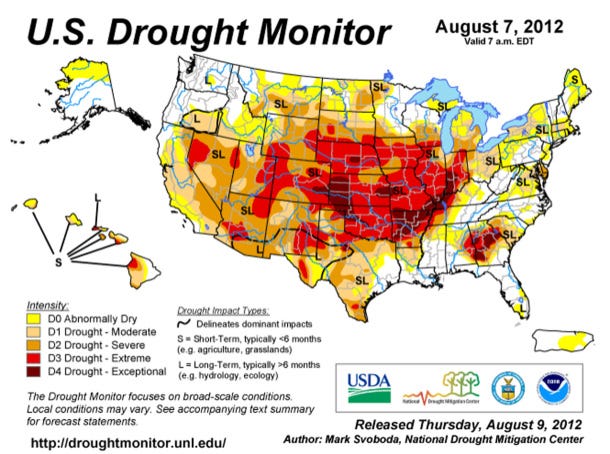

Fast forward to today: the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture released an announcement stating that nearly two-thirds of the continental U.S. is in a moderate to exceptional drought, making it the nation's worst agricultural drought since 1936. "Due to the drought, the USDA has declared 1496 counties across 33 states as natural disaster areas...As of early August, 50% of corn and 39% of soybeans were in poor or very poor condition."

Food vs. Fuel, the sequel

As a result, the food versus fuel/bioplastics debate has revived with a vengeance. It is particularly targeting the Renewable Fuels Standard mandate as a scapegoat. Under the RFS, U.S. fuel companies must this year ensure that 9% of their gasoline pools are made up of ethanol. Critics argue that this means converting some 40% of the corn crop into biofuel.

The director-general of the UN's Food and Agricultural Organization, José Graziano da Silva, has now also poured gas on the fire, writing in a Financial Times article entitled "The U.S. must take biofuel action to prevent a food crisis" that "much of the reduced crop will be claimed by biofuel production in line with U.S. federal mandates, leaving even less for food and feed markets."

Critics of the RFS are calling for a waiver of the mandate, proponents are arguing that if corn shortages arise, it's not the fault of the RFS but of the drought. In short, the debate is raging.

It's a debate that won't be resolved unti—in the case of biofuel—the commercialization of cellulosic ethanol gets truly underway, and overall, the use of food/feed crops for such purposes as fuel and plastics are no longer necessary.

After all, what holds for fuel also applies to bioplastics based on feedstocks derived from food crops, which have long been subject to criticism and debate. It's an important issue, and one that deserves to be taken seriously in the future development of biobased resins, if a transition is to be made to a bio-based economy in the future.

The debate has served to fuel interest in exploring the potential of next generation, non-food biomass as a feedstock for bioplastics production. Second generation non-food sources of biomass avoid the issues of food shortages and rising food prices. Agricultural "residue"—corn stover, wheat and barley straw, sugarcane or rice bagasse—and sawdust, paper pulp, small-diameter trees, dedicated energy crops such as switchgrass and other perennial grasses, municipal waste and household garbage are all excellent sources of second-generation biomass that are available in abundance. Cellulosic technology and (experimental) catalyst technology are just two of the routes being looked at.

The Freedonia report predicts that the next few years will see massive changes in the bioplastics industry. Hopefully, these will include the development of technologies on a commercial scale that will finally put the debate to rest.

U.S. Drought Monitor

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like