One of the main components of the seven causes of waste in the lean philosophy is eliminating excess production and excess inventory. A standing inventory was actually an excuse that condoned scrap. If you pulled parts and found something wrong with them, you simply rejected what was bad, went to the warehouse, and pulled more parts so that you wouldn’t shut down your production. Lean is all about good parts. If the warehouse is filled with good parts, none would be rejected and therefore there’s little need for any standing inventory.

October 20, 2010

One of the main components of the seven causes of waste in the lean philosophy is eliminating excess production and excess inventory. A standing inventory was actually an excuse that condoned scrap. If you pulled parts and found something wrong with them, you simply rejected what was bad, went to the warehouse, and pulled more parts so that you wouldn’t shut down your production. Lean is all about good parts. If the warehouse is filled with good parts, none would be rejected and therefore there’s little need for any standing inventory.

The book, Japanese Manufacturing Techniques, goes to great lengths to describe the “no startup costs” technique. It points to very flexible production lines that could switch from one model to the next (automotive). In another example (the workcell mentality), inexpensive dedicated production lines that only made single products is described. When production was needed, they simply turned on the lights, workers sat down, and the dedicated line was used. When production was finished, they put everything away and turned off the lights.

What is neatly ignored is the capital expense of a dedicated production line just sitting there collecting dust when it not in use. Somebody has to pay for the idle equipment, the cost of capital, maintenance, and the floor space consumed even if this were justified by the fact that there were no startup costs.

Now let’s look at an example in molding. In its simplest context, the cost of a molded part has five basic components, regardless of the volume produced:

1. Setup cost: what you had to spend to get the first good part ($100)

2. Manufactured part cost: the labor and material that was invested to actually make the part after the process was brought online ($12.50/50 parts)

3. Packaging cost: the cost of the box, bag, etc. that allowed you to ship the product to the customer ($1.00—holding 50 parts, taking up 0.5 ft2 storage space)

4. Finance cost: the cost of the money you paid (the interest) from the time you incurred the setup cost to the time the invoice was paid (assume 1%/month)

5. Storage cost: the floor space you “rented” to store your parts in the JIT warehouse ($0.75/ft2/month floor space; three-tier racks would equal $0.25/ft2/month shelf space).

For the moment, let’s assume everything is electronic so we don’t have to worry about the paperwork costs of invoicing, the parts are accepted, the yields are 100%, and the customer pays in net-30. Further assume the customer orders in quantities that are “per box” regardless of the parts per box, and the cost of the box has been set regardless of the fact we actually had to buy 500 of them.

Now look at two extreme examples.

|

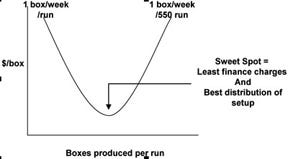

Example #1: True JIT. The customer wants one box per weekly shipment and no extra parts to be produced. To simplify the math, let’s assume the parts instantly appeared so we don’t have to get into the minutiae of financing the setup time and run time. After some simple keyboard thumping and with no finance or storage costs, the cost per box comes to $263.50 (amortizing the setup costs). Naturally, the buyer refuses to pay this price.

Want to kill a bad manufacturing policy? Follow it to the letter.

Lean is all about minimizing costs. Only the guys who read the Executive Summary or the Cliff’s Notes version think “zero setup costs” are practical. If you want to demonstrate the failure in this thinking, follow orders: Only order materials, packaging, and so forth per your “lean” schedule. Charge for your costs. As soon the buyer wants to increase the order size for the next six weeks, listen to him scream when you talk tell him the costs of air-freighting in bags of resin, premium costs of extended runs, etc.

Example #2: Economy of Scale. the buyer goes crazy with the unit cost per box, knows there’s an economy of scale, and orders a one-time lifetime production run of 550 weeks of production. The cost of the last box (having piled up storage and finance charges for 10 years) comes to $264.11, ignoring compound interest, inflation, lost opportunity, and the other snooty financial concepts. Again, the buyer refuses to pay this price, not wishing to get into variable costing structures.

If we were to vary the number of boxes run and look at the cost of the last box, we’d see a curve like the one in Figure 1. Any freshman in economics can draw this curve. With true JIT you have to eat the entire setup charge. While the setup charge is “buried” with larger volumes, the amortized finance and storage charges will eventually equal the setup charges. So the trick is to order in quantities equal to the amount defined by the bottom of the curve (the sweet spot).

You can finding the sweet spot by three methods:

1) Set up a spreadsheet of costs knowing the ideal number is between 1 and 550 and test with different-size production runs until you find the lowest unit cost. If someone is really good at spreadsheeting, you can tell the computer to go through all the combinations and find the lowest cost. Your computer can do it in a matter of seconds.

2) Find a calculus geek and ask for the derivation of the number of boxes required so that the slope of curve equals zero. He’ll come back with a pad of calculus equations that only he can understand.

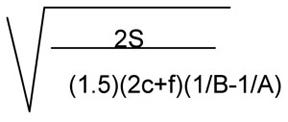

3) When you solve the last line of the formula, you’ll come out with a relatively easy square root formula shown in Figure 2 (note this is one of many economic run size formulas you can pull out of any economics or production control book), where:

S = setup cost

C = storage cost/month

F = finance cost/month

A = production rate per month (continuous run)

B = shipping rate per month

Think of the last box. It consumes 0.5 ft2 so it will be stored at $0.25/month ÷ 2 = $0.125. You will be financing the total cost of the box (box + parts) plus the storage cost every month plus the cost of borrowing the money to store the parts. Fifty pieces per box = $12.50 for the parts + $1.00 for the box + $0.125 to store it for a month multiplied by the interest rate = $0.14/month.

For those of you who can do spreadsheets, the program line is:

=sqrt ( (2*setup)/)(1.5)*((2)(storage)+finance)*((1/shipping rate) - (1/production rate)))

In this example, the sweet spot calculates out to 38 boxes (1900 parts) for a cost of $18.85/box.

The real hangup with JIT manufacturing is scheduling, because constant setups and so forth don’t account for maintenance, and a change in the delivery quantity will muck up the molder’s planning. Buyers are deluded into thinking because they don’t have to pay for setups, they can jerk the schedules around by tripling the order quantity one week and then canceling the order quantities when sales are slow.

Most molders secretly(?) have a JIT warehouse. This is where they overrun the order and then ship from their stock instead of running the mold for each shipment. This saves the molder’s scheduling, but there is always the risk that there might be a color or engineering change where all this “private” unordered stock will now be declared unusable. Buyers blow this off as the cost of doing business. Molders look at it as a dead loss.

How is this solved? Write a Min-Max purchase order. When the JIT schedule is received, you run the numbers through the equation and then produce the amount of parts you calculated. Since our production capacity is 2.4 boxes/hr, we can easily produce our run in one shift. All other things being equal, we write the PO so that our customer is liable for up to a maximum of our 38 boxes. When the inventory gets down to two or three boxes, an automatic schedule is triggered for another run, giving us two to three weeks lead time, unless you are told differently. Everybody wins; nobody loses.

Once you sit down with your bookies and figure out the cost per square foot in your warehouse, the pieces per square foot each part will consume, and your particular cost of finance, the calculation is really pretty simple for the optimum run size.

Lean is never about empty warehouses or secret “off the books” unauthorized (wink wink) inventory. Lean is about lowest cost. You cannot get away from startup costs, but with a little planning, both the customer and the molder can minimize their risks and maximize their profits.

This is the last of three articles on lean (read the first here). Consultant Bill Tobin is a regular contributor to IMM. You can sign up for his e-newsletter at www.wjtassociates.com.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like