Sponsored By

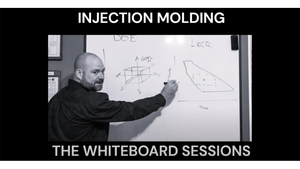

Injection Molding

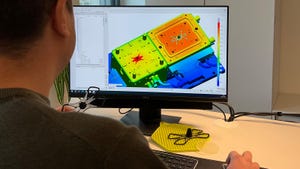

pro Edge VG nozzle

Injection Molding

New Injection Molding Nozzles Improve Gate Quality, Facilitate MaintenanceNew Injection Molding Nozzles Improve Gate Quality, Facilitate Maintenance

Hot-runner supplier Ewikon will feature an expanded selection of nozzles for side gating at NPE.

Sign up for the PlasticsToday NewsFeed newsletter.

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)