Bisphenol-A. Has an organic compound divided the world as much as this synthetic estrogen? While this chemical compound instills much controversy, anger, fear, and frustration on one side, the other side merely sees it as a protector of food that helps packaging withstand the high temperatures of the sterilization process and, overall, increases products' shelf life.

July 2, 2012

Bisphenol-A. Has an organic compound divided the world as much as this synthetic estrogen? While this chemical compound instills much controversy, anger, fear, and frustration on one side, the other side merely sees it as a protector of food that helps packaging withstand the high temperatures of the sterilization process and, overall, increases products' shelf life.

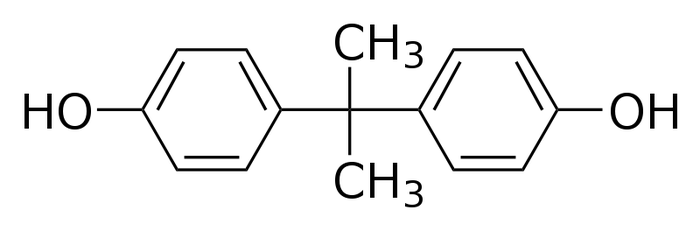

BPA is a synthetic estrogen used to produce polycarbonate (PC) polymers and epoxy resins. As such, it is present in many hard plastic bottles and containers, metal-based food and beverage cans, in addition to safety equipment, eyeglasses, computer and cell phone casings, and more.

BPA in focusPlasticsToday and sister publication Packaging Digest have combined resources for a comprehensive report on bisphenol A (BPA), including its history and future, as it relates to packaging. |

Physiologically, BPA is said to mimic the hormone estrogen and has been linked to increased breast cancer risk, obesity, and other health conditions. In addition, about 90% of Americans have traces of BPA in their urine, according to the Endocrine-Related Cancer Journal.

This is partly how BPA become a villain in food packaging, at least in some people's eyes.

"If you stop 10 people on the street, and ask them about BPA, they know right away that it's supposed to be considered bad," Stuart Yaniger, VP of research and product development at PlastiPure, told PlasticsToday. "But if you ask a follow-up question about why it's bad, expect to get a blank look because they don't know why."

Before we get into the current state of BPA and polycarbonate for packaging, along with looking at new technologies to replace PC, let's look back at this chemical's history and how it became the cornerstone of controversy.

History of BPA

It's well documented that BPA was first synthesized by chemists in 1891, however, the first mention of BPA was made in a scientific paper in 1905 by Thomas Zincke of the University of Marburg, Germany.

It wasn't made relevant until the 1950s when the thriving plastic industry underwent a technology revolution with the introduction of new materials, design techniques, and processes, such as injection molding.

Dr. Hermann Schnell of Bayer invented polycarbonate (PC) resin in 1953, just one week before chemist Dr. Daniel Fox of GE made the same discovery while working on developing a new wire insulation material. Both found a gooey substance that hardened in a beaker, and despite their best efforts, they could not break or destroy the material. They were equally impressed by the toughness of the material.

While both companies applied for U.S. patents in 1955, they agreed that the patent holder would grant a license for an appropriate royalty, which allowed both companies to concentrate on developing the polymer.

The main polycarbonate material is produced by the reaction of BPA and phosgene COCl2. Unlike most plastics, polycarbonate can undergo large deformations without cracking or breaking.

Polycarbonate was initially used for electrical and electronic applications such as distributor and fuse boxes, displays and plug connections, and for glazing for greenhouses and public buildings. PC's characteristics became popular for many other applications, including plastic bottles and linings for metal-based food and beverage cans.

Polycarbonate was initially used for electrical and electronic applications such as distributor and fuse boxes, displays and plug connections, and for glazing for greenhouses and public buildings. PC's characteristics became popular for many other applications, including plastic bottles and linings for metal-based food and beverage cans.

The use of PC for food packaging received original approval in the 1960s by the FDA under its food additive regulations.

The discovery

Throughout the decades there were various studies with regards to BPA, but it wasn't until Dr. David Feldman, a medical doctor, and a professor at Stanford University, made a discovery that changed the discussion of PC and BPA forever.

"We weren't looking for this," he said. "It was basically an accident."

During the early 1990s, Dr. Feldman conducted studies on estrogen activity. In 1992, Feldman and his team discovered what looked like an estrogenic molecule when they were growing yeast in plastic flasks. It turned out it was not the yeast synthesizing the estrogen, but rather it was leaching from the plastic. The team then performed an experiment without having the yeast in the flask, and they found there was still this estrogenic molecule in the medium, which they then identified the estrogenic molecule as BPA. They found it was coming from the plastic flask and was not present when they did the experiment in glass flasks.

"We realized that we had identified a molecule that was leaching out of the plastic that, due to its estrogenic hormone-like properties, was potentially dangerous to people eating out of containers made of this type of plastic," he said.

Once they made the connection between polycarbonate, BPA, and estrogenic activity, Feldman and his team contacted a major producer of PC, the former GE Plastics, now Sabic Innovative Plastics, the producer of the Lexan brand PC.

It turns out the company had already looked into the potential leeching issue, but after using their own methods, the company said they couldn't find any estrogenic activity.

While Feldman and his team wrote about their findings, he moved on from conducting research on BPA, but he continued to study findings out of an interest.

"We are still in the same place we were 20 years ago," Feldman said with a sigh. "We are still exposed to this molecule in our food supply, it's in our urine. The question of how bad it is, well, it's still debated."

Initial bans

Bans began with what some called "defending" the most helpless of people—infants.

A 2008 report by the U.S. National Toxicology Program (NTP) found "some concern for effects on the brain, behavior, and prostate gland in fetuses, infants, and children at current human exposures to bisphenol A," with that exposure coming from PC baby bottles and infant cups.

Once baby bottles that were microwaved were found to release BPA into infants' milk, the European Union and Turkey banned the chemical from baby bottles in 2008. Canada also banned BPA in bottles, with Health Canada concluding that chemical was "'toxic to human health and the environment."

Denmark has banned BPA in all baby food products, and the Japanese canning industry has replaced its BPA-containing resin can liners. The U.S. still allows BPA in baby bottles, but 11 U.S. states have prohibited the use of BPA in children's products.

Denmark has banned BPA in all baby food products, and the Japanese canning industry has replaced its BPA-containing resin can liners. The U.S. still allows BPA in baby bottles, but 11 U.S. states have prohibited the use of BPA in children's products.

The FDA states on its website that it, "supports the industry's actions to stop producing BPA-containing baby bottles and infant feeding cups for the U.S. market, along with facilitating the development of alternatives to BPA for the linings of infant formula cans."

The FDA vs. the NRDC

For decades, the U.S. government has claimed low doses of BPA are safe.

Environment advocacy group The Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) calls itself, "the earth's best defense."

In 2008, the NRDC took a stand against BPA as a whole, and asked the FDA to eliminate the chemical from all food packaging.

"Even then, we were confident that there was not enough evidence to conclude that BPA was a safe chemical and therefore should not be in our food supply," said Sarah Janssen, Sr. scientist in the public health program of the NRDC.

When the agency didn't take action, the NRDC sued the FDA in 2011, and asked the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York to compel the agency to respond. Later that year, the court issued a consent decree requiring FDA to make a final decision on NRDC's petition by March 31, 2012.

March 31 rolled around, and the FDA ultimately decided not to ban BPA from food packaging. A FDA spokesperson said the decision was "not a final safety determination and the FDA continues to support research examining the safety of BPA, and will make any necessary changes to BPA's status based on the science."

"The FDA denied the NRDC petition because it did not have the scientific data needed for the FDA to change current regulations, which allows the use of BPA in food packaging," the agency stated.

While the FDA said some studies have raised questions as to whether BPA could be associated with a variety of health effects, the agency still has "serious questions about the studies, particularly as they relate to humans and the public health impact of BPA."

FDA is working toward completion of another updated safety review on BPA this year to include all relevant studies and publications, and is also working with the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, which has invested $30 million into research on BPA.

Even before the FDA made its most recent decision, several U.S. companies have already started to remove BPA from its food packaging, such as Hain Celestial, ConAgra, H.J. Heinz, and, to a lesser extent, General Mills and Nestlé. Other U.S. food companies such as Eden Foods, Muir Glen, Edward & Son, Trader Joe's, Vital Choice, Wild Planet Foods, Oregon's Choice Gourmet, and Eco Fish, among others, also package all or part of their product in BPA-free containers.

In addition, some U.S. canned-food manufacturers are voluntarily removing BPA from can linings.

Ron Sasine, senior director of packaging for Walmart, said the retail giant is following the BPA issue extremely closely, and remains supportive of work by government and industry on packaging alternatives that are safe for its customers. Shortly after NTP's report, Walmart vowed to stop selling baby bottles made with BPA in its U.S. stores.

Sasine said the company sells other products where BPA continues to be part of the production cycle, including some of its packaging. For example, Walmart still sells food and beverage cans that contain epoxy resins made with BPA, which are FDA approved.

Janssen believes the FDA made the wrong call when it did not ban BPA.

"BPA is a toxic chemical that has no place in our food supply," she said. "The agency has failed to protect our health and safety—in the face of scientific studies that continue to raise disturbing questions about the long-term effects of BPA exposures, especially in fetuses, babies and young children."

Opposite sides of the field

To say opinions vary greatly regarding the health effects of BPA is probably the understatement of the century. Some studies state there are no health concerns, while others claim there are a number of health effects.

For example, recent research states that even low levels of BPA can cause harm in the mammary gland, prostate tissue, and brain. In addition, some studies have found links between BPA and cardiovascular disease, obesity, and possibly diabetes.

At the same time, many regulatory bodies around the world have assessed the science on BPA and determined that BPA is safe for use in food contact products.

An international panel organized by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concluded that the, "initiation of public health measures would be premature." The panel also concluded that it is difficult to interpret the relevance of studies claiming adverse health effects from BPA.

Nevertheless, many countries have opted to uphold bans of BPA in consumer products due to concerns over the potential effects of BPA exposure. For instance, France voted to ban BPA in all food containers by Jan. 1, 2014, and by Jan. 1, 2013, for food packages, materials and containers for infants and young children.

"It's not an open-and-shut case," Stanford's Feldman said. "But it makes me somewhat depressed about the idea that 20 years after our original findings, in terms of the regulatory system, everything is still relatively the same."

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like