Bioplastics: Coming to an RFQ near you

Hidden in the new material hoopla is that much of the real bioplastics excitement surrounds materials that are just “greener” versions of polyolefins, polyamides, or other thermoplastics. OEMs and brand owners are making clear they intend to specify these materials.

January 28, 2010

Hidden in the new material hoopla is that much of the real bioplastics excitement surrounds materials that are just “greener” versions of polyolefins, polyamides, or other thermoplastics. OEMs and brand owners are making clear they intend to specify these materials.

It is difficult for many processors to get excited about bioplastics, which many have filed away as a group of materials little is known about except their price (high) and their properties (water and heat resistance? Set your sights low). Oh yes, and limited capacity means they are tough to find even if you do want them.

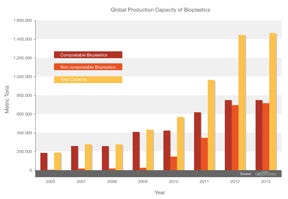

But negative perceptions are bound to dissipate in the next two to five years as vast supply enters the market, as the body of knowledge on processing these materials increases, and as additives suppliers and compounders busily work on improving their mechanical properties. Based on recent announcements, the European Bioplastics trade group estimates production capacity of bio-based plastics will increase from 360,000 tonnes in 2007 to about 2.3 million tonnes by 2013.

|

The pace of development also is so rapid that a processor who tested, for example, polylactic acid (PLA) just two years ago, and was disappointed, probably needs to revisit the material. “If you’ve tried these materials before and failed, try again,” urged Andy Sweetman, global marketing manager of sustainable technologies at Innovia Films, a €400 million/year (about $600 million/year) films processor, as well as chairman of the European Bioplastics’ board of directors. He made his comments at the European Bioplastics conference in Berlin, Germany in November. The conference drew a global audience of 380, a significant feat in a recession where conference and trade show attendance has plunged.

Improve what’s already there

But even for processors who understandably get lost in the bioplastics’ acronym soup—PLA, PHB, PHA, and all of the rest—there is little need to wait for some of the most interesting developments, which focus not on developing new materials but instead on lessening the environmental impact of the materials that processors and their customers already purchase and use, such as polyethylene, polypropylene, and polyamide. Also speaking at the conference was Hans-Josef Endres, a professor at the University of Applied Sciences & Arts in Hannover, Germany, who said industry’s research and development efforts should therefore focus on “improving what’s now available,” specifically citing “the Braskem approach.”

Braskem, the giant Brazilian plastics and chemicals supplier, is Latin America’s largest plastics supplier and a fast-growing force on the global stage. As reported previously, the supplier is hard at work improving the process to derive ethanol from sugarcane; ethanol, converted to ethylene, forms the basis for polyethylene (PE).

Rui Chemmes, director of Braskem’s PE operations, also speaking in Berlin, said the ethanol-based polyethylene has exactly the same characteristics as PE derived from petroleum. Plus, he added, it is nine times as efficient to derive ethanol from sugarcane as from corn, and 4.5 times as efficient compared to ethanol derived from sugar beets.

“Sugarcane is a 4m-high plant” that grows quickly and with little assistance, he explained. Other environmental benefits include its work as “a real vacuum cleaner of carbon dioxide.” One pound of petroleum-based PE releases 2.5 kg of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere, he said, whereas the same amount of sugarcane-based PE captures that same amount of the gas.

Chemmes said the supplier has developed low-density, linear low-density, and high-density polyethylene grades from the ethanol, and even a polypropylene, though this last as yet has only been achieved on a lab scale. This year the company will start a 200,000-tonnes/year-capacity plant for PE, he said, adding quickly that this smaller facility is “just a start.” According to Chemmes, the next facility will be capable of output of 1 million tonnes or more annually. “We want to be mainstream” with these materials, not a niche, he stated.

Soon after the event, carton-creating giant Tetra Pak tasked Braskem to supply it with high-density polyethylene (HDPE) derived from sugarcane for closure molding. Starting next year, Braskem will begin supplying Tetra Pak with 5000 tonnes/year of the “green” HDPE, a volume Tetra Pak says is a bit more than 5% of its annual HDPE requirement. Linda Bernier, director of corporate PR at Tetra Pak, told MPW that the company injection molds some of its closures but also buys them on the market, and has not yet decided who will process the Braskem material.

That beverage company in Atlanta

Five thousand tonnes is barely a drop in the plastics market ocean, but there is a huge consumer-driven wave en route that will drive demand much higher, very quickly, predicted Cees van Dongen, a senior member of The Coca-Cola Co.’s global Environment, Health & Safety Council. In a panel discussion at the conference, he elaborated, saying, “We expect a big wave. We think commodity plastics will be substantially replaced by bioplastics,” with consumers driving the shift. While acknowledging that change already is swift, “The wave will increase in both height and speed” in the coming years, he added.

Probably no brand owner will make as big a splash as Coke, which, like Tetra Pak, intends to start by replacing some of its petroleum-based thermoplastics with plastics sourced from renewable materials. In a project that entered the market in the past weeks, the beverage bottling giant began a limited trial in western North America and Denmark, replacing up to 30% of each bottle’s polyethylene terephthalate (PET) with material sourced from renewable resources.

Van Dongen said the program is the first along a path to greater sustainability. In the U.S., about 30% of the bottles’ weight will be made from mono-ethylene glycol (MEG) derived from sugarcane and molasses; in Denmark the percentage of plant-derived MEG will be half that but those bottles will include 50% postconsumer recyclate (PCR). He said there is not enough PCR-PET available in the western United States for use in these bottles, as most of the PET collected in that part of the U.S. is exported to Asia.

MEG and purified terephthalic acid (PTA) are the building blocks of PET. Ethanol derived from sugarcane will be fermented to create the bio-MEG, he explained. According to Coke, the PlantBottles will be the first beverage bottles that include content derived from renewable resources that still can be recycled in standard PET recycling streams.

The beverage bottler’s goal is to use 2 billion of the bottles by the end of 2010, in a variety of products but including its flagship Coca-Cola band. Future launches are being planned in other markets, including Brazil, Japan, and Mexico, and for China’s Shanghai Expo in 2010.

Based on total tonnage, about 55% of Coke’s packaging is PET, Dongen said. Because PET bottles’ design has already been nearly optimized to limit weight, and because the material’s manufacture is the most negative aspect of the material from an environmental viewpoint, the best way to limit the environmental impact of PET bottles is to replace the PET, he said. The PlantBottles are indistinguishable from standard PET bottles, he added. The goal, he said, is to develop feedstocks suitable for 100% bio-based PET.

However, Dongen said Coke sees little future for the current crop of biodegradable bioplastics as primary beverage packaging. “For the next five to 10 years, we don’t see biodegradable plastics as an option for our bottles,” though the company is looking closely at their use for secondary and tertiary packaging, he said.

What do all of these developments mean for processors? Change can be confusing, but it also is notorious for creating opportunities. The examples above are in packaging, but in fact just as much development is under way in increasing the renewably resourced material content in plastics destined for durable goods. It seems a bright future awaits processors able to track and take advantage of the many developments. —Matt Defosse

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like