Sweet success in sustainability

With apologies to Kermit the frog, it really is easy being green, as Plastikos found out when it began efforts nearly two years ago to reduce, reuse, and recycle. Are the efforts paying off? And just how expensive is it for a custom injection molding operation to become green?

July 30, 2009

With apologies to Kermit the frog, it really is easy being green, as Plastikos found out when it began efforts nearly two years ago to reduce, reuse, and recycle. Are the efforts paying off? And just how expensive is it for a custom injection molding operation to become green?

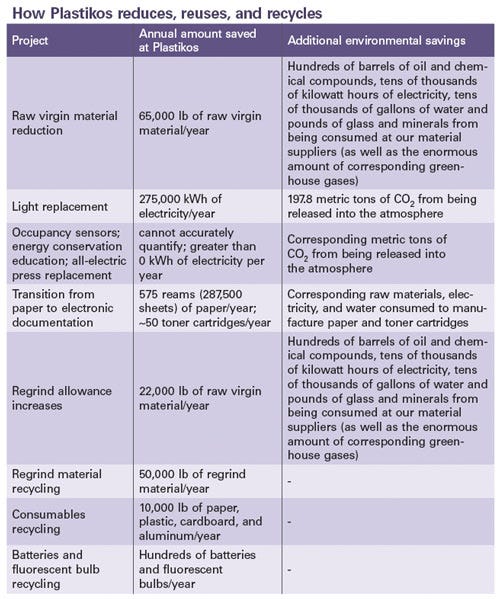

When Plastikos Inc. started its “green” initiative, it looked at the low-hanging fruit first. “We started out with things that were easy to implement and provided quick returns, such as the lighting,” says Ryan Katen, engineering manager for this 27-press custom injection molding company in Erie, PA. “It was simple to do, didn’t require a lot of planning, and there’s a significant return reflected in our electricity bill, especially with a plant the size of Plastikos.”

|

Like most plastic processing plants, the 60,000-ft2 Plastikos facility burns a lot of electricity to support its operations. In 2008, the company consumed more than 3.157 million kWh of electricity. It converted its main molding floor from T12 to T8 fluorescent technology with electronic ballasts. The project cost approximately $25,000 to complete, but resulted in electricity savings of 150,000 kWh in the first year. This in turn saved 108 metric tons of CO2 (using an EPA calculation) from being released into the atmosphere. Also, Plastikos installed occupancy sensors on fluorescent bulbs in the breakrooms, supply closet, offices, and restrooms.

Using the savings realized from installing the lighting and sensors, the company invested in other initiatives that focused on significantly reducing the company’s carbon footprint, rather than on ROI. One of those—and one of the biggest costs for a custom molder—is raw materials.

The three Rs

While the use of regrind and the percentage allowed back into the parts are dictated by its customers, Plastikos found better ways of handling the regrind. Where regrind was allowed in molded parts, Plastikos worked with its customers on the allowable amount. In some cases, says Katen, Plastikos was able to increase the allowable percentage of regrind from 25% to 50% or from 10% to 25% without impacting the part’s performance.

In spite of those efforts, Plastikos still produces more regrind than it can use internally. Prior to the green initiatives, the company used to dispose of its regrind, sending it to the landfill. “We began to look for places that would buy our regrind, which does add a bit more work to the process,” says Katen. “We have to produce clean regrind if we’re selling it, so we have to clean the grinder after each use. And it takes warehouse space to store it in boxes or gaylords until we can find a buyer. We find it’s difficult to find buyers for the low quantities we usually have.”

Plastikos runs smaller electrical components in 25- to 130-ton machines that use a lot of engineering-grade resins, particularly Vectra E130 LCP (from Ticona), which represents 80% of the plastics the company runs. Many resin recycling companies won’t take LCP resins, Katen notes. “Instead of throwing [scrap material] away and paying Waste Management to haul it to the landfill, we can get someone to pay us to haul it away,” Katen states. Despite the extra effort involved, the results are worth it for the molder: 50,000 lb/year of regrind is now recycled instead of being landfilled.

In addition to resin reuse and recycling, Plastikos engineers and toolroom employees developed a proprietary technology that significantly reduces the amount of virgin resin consumed during the course of production and eliminates waste. “It took a lot of engineering work to figure out how to make this proprietary process work, but it saves a lot of money in terms of raw material,” Katen says. Total raw material savings attained thus far are in excess of 15%, which equates to more than 65,000 lb of raw material saved annually.

Other moves Plastikos has made to green its operations include:

• Starting replacement of all its old desiccant dryers with state-of-the-art compressed-air dryers, a project that will take about six months.

• Reducing its usage of paper and other consumables. “We used to print a lot of paper; now we do it electronically,” says Katen. “We’ve found it easier to control electronic documents than track 100 pieces of paper. And we save on toner, too.”

• Recycling all consumables—more than 10,000 lb of paper, plastic, cardboard, and aluminum were recycled in one year.

Getting buy-in

With 80 employees, getting buy-in for these initiatives wasn’t easy, Katen admits. “It’s tough. People don’t like to change how they do things even if it’s for the right reason,” he says. “We just use constant reminders, and provide examples of the cost of throwing things away vs. recycling. It’s actually cheaper to be green and recycle than to throw things away, but it’s a learning curve because they’re comfortable with the old way. We keep driving it home to get everyone to buy into it. There have definitely been some painful steps along the way.”

The company’s efforts are paying off in other ways as well. Plastikos recently received the Young Erie Professional’s inaugural “Green Company of the Year Award” in the for-profit category.

“One initiative won’t make a significant difference,” Katen concludes, “but doing a lot of different things adds up to a sizable savings.”

|

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like