How Plastic Foam Makes Nukes Safer

Trucks transporting nuclear missiles for maintenance have a secret weapon to ensure their safety — plastic foam.

February 5, 2024

Growing up in Minneosta during the Cold War — that was the Seventies and Eighties for me — intercontinental nuclear weapons were on most people’s minds more than they are today. At least once a year, there would be an article in the papers about how important a target Minneapolis and St. Paul were for the Soviet Union, with us commonly listed as the #5 city in the country, right after DC, New York, LA, and Chicago. Why so high? For quite a while, the Twin Cities were the US home for supercomputing companies – Cray Research and CDC — a necessary tool for weapon development. (Those companies’ remnants now operate at greatly reduced capacities, so the threat is considerably less.)

I spy a . . . missile silo

Beyond having targets on our hometown, everybody knew the Dakotas and other prairie states were loaded with US missiles. I’d always be on the lookout during family road trips to see if I could find a missile silo (as if they were placed within eyesight of the interstates!). I never did see one (that I’m aware of).

Like most people, I just assumed that the missiles were built, moved to their hole in the ground, and then just sat waiting, hopefully never to be used. I recently discovered that’s not the case, and that plastic foams play a (potentially) important role in that story.

It turns out nuclear missiles need a lot of care and maintenance, much of which cannot be performed on location. So, the missiles need to be taken to other locations across the country where the people, equipment, and facilities are. Transporting a nuclear missile must be done carefully — not because of the risk of an unintended explosion, but because certain unsavory groups would love to get hold of such a weapon. Getting it while it’s in a silo would be difficult; hijacking it while it’s on a truck would be much easier.

Specially designed 18-wheelers

This is such a big concern that the US government established the Office of Secure Transportation for just this role. Information about its activities is understandably hard to come by, but the missiles are moved using a “specially designed” 18-wheeler escorted by SUVs with armed security agents that are authorized to use deadly force.

"Specially designed" includes:

12-inch-thick walls;

run-flat tires;

nozzles to remove the air and replace it with noxious chemicals;

an automatic sanding device in case the roads are slick;

an autonomous-firing weapon system.

The trucks are called Safeguards Transporters. They’re made by Peterbilt and from the outside look pretty nondescript. They have government plates, don’t exceed 65 mph, and don’t travel in bad weather. So now you know what to look for on your next road trip.

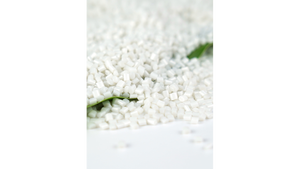

Tipping activates plastic foam

What about the polymer foam? Ah, yes. The trailer has been designed so that if it tips too much, it will dispense a quick-reacting polymer foam. It’s not clear whether the foam is designed to fill the truck and block access to the cargo or if it is a sticky foam that is meant to restrict the movement of the attackers (or both). Regardless of the intent, I’d guess it’s a polyurea. (Polyurethanes can react quickly, but to paraphrase Newton, "For every urethane reaction, there is an equal and faster urea reaction.")

I’m sure there are other defensive measures that are not disclosed. There is a balance between having enough information out there to strongly discourage anyone from attempting an attack, and too much information so that a real weakness can be found. What I listed above is pretty impressive already.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like