Up in smoke: When your molding facility burns

May 27, 2002

|

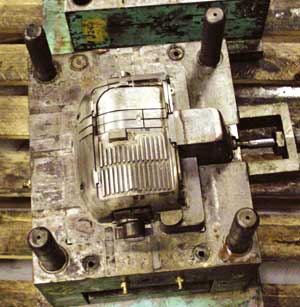

Fire and sprinkler water caused damage to more than 500 molds at Chris Kaye Plastics. Problems collecting insurance reimbursement has forced the company to pay out of pocket to get the tools running again. |

Up in Smoke" was a funny movie. But there's nothing funny about what happened just over a year ago to 53-year-old Chris Kaye Plastics in St. Louis, MO, when fire devastated the molding facility. Inside were more than 500 molds.

The fire knocked out electric service and triggered 150 sprinkler heads. The entire mold storage area was showered with water and covered with dense black smoke, leaving all of the tools coated in black goo. The molds suffered severe corrosion damage. Some 270 molds belong to Chris Kaye, from which it produces a line of proprietary consumer products (hangers, for example) that the company sells to various retailers, including Wal-Mart. Another 250 or so of the tools belong to Chris Kaye's customers.

President and son of the founder, John Kacalieff, thought that having insurance would get the company back up and running. However, when Kacalieff turned in a $1.3 million estimate to refurbish the damaged molds, the insurance company balked. "They offered us $150,000," says a disheartened Kacalieff. To make matters worse, the insurer told him that it won't pay to refurbish any molds owned by Chris Kaye that haven't run parts in 10 years.

"Our survival depends on a reasonable settlement for these molds," says Kacalieff, who has spent hours categorizing molds, assessing damage, and refurbishing at his own expense molds needed to fill current orders—all while trying to convince the insurance company that the molds, even the old ones, have value.

"We've already put [in] from several hundred dollars up to $6000 to get all the corrosion out of the molds for parts we have orders on," says Kacalieff. "Now we have to prove the value of the molds is greater than the cost to restore them."

Expect the Worst

Most custom molders don't keep the molds they own or run for customers in a protected area. Rain Bird's molding plant in Tucson, AZ is an exception. When the company renovated a manufacturing facility there several years ago, it built a fireproof room with a steel door to protect the molds from water and fire damage. This proprietary molder of lawn and garden irrigation systems knows that a fire could devastate the company's product lines, so it took extra precautions in protecting its molds.

Determining both a mold's value and the molder's liability if the mold is owned by a customer is another sticky issue. Bill Tobin of WJT Assoc. (Louisville, CO) is an industry consultant and a frequent contributor to IMM. He says valuation and liability have always been gray areas for molders. "The industry standard is that anything held in consignment is just that," says Tobin. "When the fire department comes in with the hoses and water, who's liable for the damage to molds?"

|

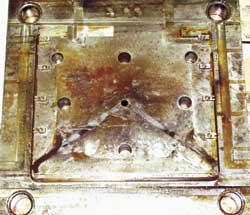

Rain Bird stores its tools in a fireproof room to prevent damage like this mold suffered in a fire at Chris Kaye Plastics. |

Tobin, who often serves as an expert witness in cases involving molds, notes that "anything that is yours, i.e., molds, is an asset with the potential to make money." He suggests that molders produce paperwork such as purchase orders or invoices to prove that the molds were valid tools with which to make money, and that customers say, "Yes, we do require these parts from time to time," even if they haven't purchased parts from the molds for several years.

"It's messy with a fire," says Tobin. "The name of the game for the insurance companies is to delay this as long as possible, but by their delay they'll probably put [the molder] out of business. Of course, that has the potential to increase the loss."

Preserving the family business is foremost in Kacalieff's mind. He recounts that his father started the company in 1949 with a Van Dorn Model 1 molding press that he put in a rented shoe shine parlor and began molding parts. The elder Kacalieff is now 80 years old, and saving the business is paramount to his son.

What Can a Molder Do?

Having enough insurance on molds in your facility is critical to the preservation of your business after a fire. Orv Schnieder, ceo of InsurAmeriCorp in Grand Rapids, MI, specializes in insuring molding and moldmaking businesses. He says that molders should insure their equipment, work in process (inventory, and so forth), and all raw materials.

Also, because most custom molders do not own the molds they use in manufacturing, there is in most cases a clause that covers "molds of others."

"If those are destroyed, there is separate coverage," says Schnieder. "If in fact [Kacalieff] doesn't have this specific clause, the molds should still be covered in his regular contract."

Another helpful strategy is to make sure that the insurance agent or underwriter knows the molder's business. "The underwriter should know the particulars of each company's business, and not just write a standard contract," Schnieder advises.

Kacalieff says that custom molders are between a rock and a hard spot when it comes to storing another company's property. "When you look at it, if you add onto your books another X million dollars as property of others, there goes your insurance premium sky high."

Many of Chris Kaye's customers have insurance on their molds, but he's hesitant to go to them and tell them they have to file a claim. "It puts you in an awkward position to have to go to customers and ask them to file a claim," he says, "but I don't know what else to do. [The insurance company] is telling us it won't pay anything on molds we don't own."

Contact information |

You May Also Like