July 12, 2021

For the plastics supply chain, most of 2021 has felt like a never-ending tightrope walk. Demand is strong as consumers and economies take steps to re-emerge from pandemic conditions. However, supplies of raw materials and labor are constrained and getting costlier, and the ability to move product is challenging.

Given a quiet summer and fall, there is substantial likelihood that supply chains will adapt and market conditions will find balance by end of year. But there is a minefield to navigate before we get there, and that is the Atlantic hurricane season.

Forecasters of this year’s hurricane season expect above-normal activity. That seems on point as of this writing with five tropical systems having formed since the season began June 1.

Based on historical data, the National Weather Service estimates that Texas’ and Louisiana’s yearly odds of being affected (brushed by or hit) by a hurricane – a tropical system with sustained winds greater than 74 miles per hour — at 1-in-3. About 20% of the Texas-Louisiana coastline (particularly south of Corpus Christi, TX) is not dotted with chemical/polymer plants or refineries, so factoring that out leads to about a 1-in-4 chance each year that a hurricane will strike a section of the Gulf Coast key to the plastics supply chain.

History lessons.

Chemical plant and refinery operators are accustomed to those risk odds and are adapted to the challenges operating in a hurricane-risk environment. Gulf Coast refineries, crackers, and chemical derivative plants weather the situation via orderly shutdowns ahead of the storm, assessment of any damages after it passes and then making relatively quick repairs to get back into operation. Historically, the plants were back up and running within a couple of weeks, although particularly devastating windstorms such as hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005 led to multi-month outages. More recently, Hurricane Harvey in 2017 brought historic flooding to the Texas coast, while Louisiana in 2020 was subjected to five landfalling hurricanes. Refineries and chemical plant production were affected, but only for a short period – especially in comparison with winter weather events such as Winter Storm Uri’s arctic blast this past February.

There are no worries of another Uri coming through in the next couple of months, although those of us on the Gulf Coast will gladly take a summertime cool front. Hurricanes are a different matter. Should a major tropical weather event occur on the Texas-Louisiana coast this storm season, the net effect on polymer production and pricing would buck previous norms of short-term market blips and instead resemble what happened with February’s winter storm — or be worse.

Prices for materials would rocket higher from a much higher baseline of current pricing than where we were at earlier this year during Uri.

Consider the following from market data and insight provider Chemical Data (CDI), a part of ICIS:

US high-density polyethylene (HDPE) contract prices as of June had reached double their historical average level.

US polypropylene (PP) contract prices in June broke the record high established in February following the Texas Gulf Coast freeze and are close to being three times as high as they were a year ago

Freely negotiated contract prices (i.e., those not tied to upstream feedstock formulas) for US polyethylene terephthalate (PET) have risen 25% since January and are up almost 43 percent from their 2020 average.

US June polystyrene (PS) prices were about 63% higher than their 2020 average, and that was with a month-on-month drop in contract prices from May.

Drivers of these price rises have fairly been ubiquitous across commodity polymer markets. Leading the charge has resilient demand from consumers for packaging and single-use plastics, followed closely by production from pandemic-related shutdowns and weather-related outages. And then there are the myriad logistics issues faced by the entire plastics supply chain with displaced containers, sky-high demand, and even loftier freight rates.

Part delays problematic.

Hurricane-related price spikes for resins have typically been short-lived at two to three months as polymer plants on the Gulf Coast are built to make repairs from tropical weather in relatively short order. But repairing hurricane damage this season may not be as easy a task as in previous years due to manufacturing issues across supply chains and the disrupted logistics of moving needed parts. Such parts are not lying around on department store shelves. They need to be specially made, and that might be a problem as backlogs of orders remain elevated according to the Institute of Supply Management (ISM). In fact, backlogs for fabricated metal products and computer and electronic products all had their delays increased strongly in June, according to the ISM — not at all a good sign if you need some plant parts made on the fly. Thus, returns to operations could resemble more the 30 to 45-day process seen in February with Uri than the 7-21-day process seen with typical Gulf Coast tropical weather over the last several years.

That would have a significant effect on resin supply over a longer time period and would be bullish on pricing.

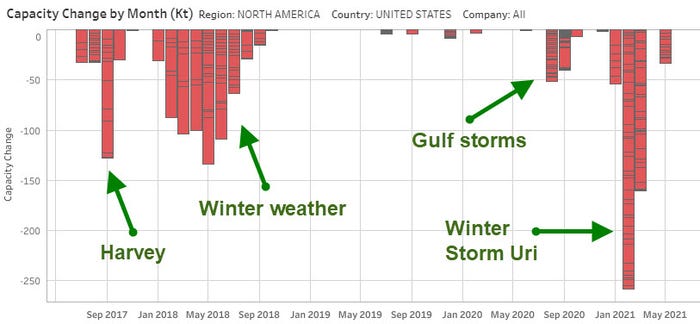

The graph above from the ICIS Live Supply Disruption Tracker shows how unplanned outages from weather have left their marks on chemical markets in the last four years, with this chart focused on HDPE production.

Resin markets sit at a very dicey stage the COVID recovery. Make it through hurricane season without incident and the supply chain has an excellent chance to balance supply and demand heading into 2022. But there is a legitimate chance of about 25% that a storm will knock the wind out of the market, and perhaps do much worse. Raw material scarcity and high-price volatility in chemical markets would have significant detrimental effects on supply chains and end products, adding fuel to mounting inflation fears and possibly even leading the way towards an economic downturn.

It is not out of the realm of possibility.

Resin plants may not be more susceptible than normal to hurricane damage right now, but the markets they serve are vulnerable. Still, while there is a 1-in-4 shot of a hurricane affecting a portion of the Texas-Louisiana coast home to those facilities, that also means there is a 3-in-4 chance of no hurricane effects at all. The market needs those odds to hold up.

Jeremy Pafford, head of North America market development, drives ICIS’s business development strategy for the US, Mexico and Canada. As well, he represents ICIS to chemical and polymer markets to showcase ICIS expertise. His role draws upon his experience in leading engagement efforts by the Americas team over the last several years.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like