Mold design wizardry goes full throttle

January 1, 1997

When awards were handed out in the most recent SPE Automotive Innovation design competition (December 1996 IMM, p. 48), it was hard to decipher why certain finalists went away empty handed. For example, one such process nomination involved "tuning" a mold to compensate for the way plastic cools in order to maintain tight tolerances and flatness. Unusual? We think so. Effective? You decide.

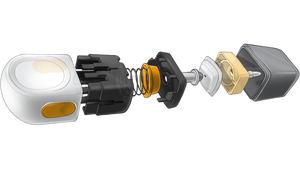

Custom molder Tomco Plastics (Bryan, OH), Ford Electrical and Fuel Handling Div. (EFHD), and resin supplier Phillips worked together to design and produce a glass-filled PPS intake manifold throttle control (IMRC) housing for the '97 Lincoln Mark VIII. Briefly, the IMRC restricts air flow in an engine's intake system so that air velocity increases at low engine speed for more efficient combustion; at high speeds, the throttle valves are opened for maximum air flow and power.

IMM spoke with Bob Wisler, market development manager for Tomco, who confirmed that the IMRC housing was a team effort among all parties involved: "We had dedicated engineers to work with at Ford, starting with Walt Fedison (lead engineer, EFHD), and the team collaborated together on every aspect of this project. This shows what can happen when your agenda is to manufacture a quality part that saves money."

To match the flatness of machined aluminum, Tomco has developed a creative way to achieve the tolerances. Rather than making the plastic conform to dimensions, explains Wisler, Tomco applies a proprietary process to contour the mold so that the plastic part will "cool" itself to the required flatness. Starting with a steel-safe mold that could be contoured later, the team produced hundreds of parts. Mold cavities contained perfectly flat surfaces at this point, and owing to the material's nature, the parts warped slightly upon cooling. Tomco engineers then took the detailed layout data from these parts and ran it through a computer program developed in-house that converts the data to mold dimension. Toolmaker Kellems & Coe received the required dimensions and cut them into the mold steel, resulting in molds "tuned" to compensate for warpage.

Tomco then began production on a 300-ton Van Dorn HT. Ford thought that the 1-inch-thick parts needed a higher tonnage machine, Wisler recalls, but Tomco's injection molding expertise resulted in a flat, 3-mm-thick PPS part weighing about 1 lb. Parts hold tolerances to .20 mm for sealing surface heights and .25 mm for the injector pod true positions, matching the accuracy of former machined aluminum versions. Bottom line: the unconventional approach saved Ford 30 percent in both weight and cost.

Says Wisler, "It wasn't just the computerized mold contouring process, it was the can-do attitude that said we know we can hit tolerances this tight. We feel it's our job to understand the polymer and its properties, plus how it reacts with the proper injection molding process. When you start molding something for dimensions' sake only, you sacrifice both product and process integrity. We mold the product for the product's sake. As much as possible, we needed to be able to mold a stress-free part, letting the material shrink and warp the way it wants. Our history with these types of polymers proves that the parts will shrink the same way every time."

On the drawing board at Tomco are several related projects: a 2-inch-thick version of the IMRC for another Ford engine; another manifold component; and fuel rails. "We apply this technology to everything we do, but we've never had a part this complex with drop-in machined metal tolerances," Wisler notes.

You May Also Like