Plastics Are Inert, Indigestible, Non-Toxic, and Widely ‘Myth-Understood’

Allan Griff, consulting chemical engineer, columnist for PlasticsToday, and self-professed realist, came across an article in MIT News that contained a misleading image and even some errors. He shares his thoughts.

December 6, 2022

I received a report on MIT research involving the use of porous minerals with a cobalt catalyst to make propane from scrap (recycled) polyolefins.

Porous minerals (zeolites) are well known. If researchers can use their pore size to produce 3-carbon molecules (propane), that's newsworthy. But it begs the question of how much 1-carbon (methane) and 2-carbon (ethane) get through and what you do with them.

The article also implies that polyolefins are pollutants, which is wrong because they are not toxic in their normal solid form — very strong C-C bonds, long chains, low reactivity. Chemically, they are more like fats, but simpler. There are no phthalates or BPA. I'd worry more about the toxicity of cobalt than polyolefin plastics.

Toxicity of solid plastics is a popular but false image based on the human need to resist science so that we can believe in the impossible, which goes back to the comforts of infancy when nothing can be explained.

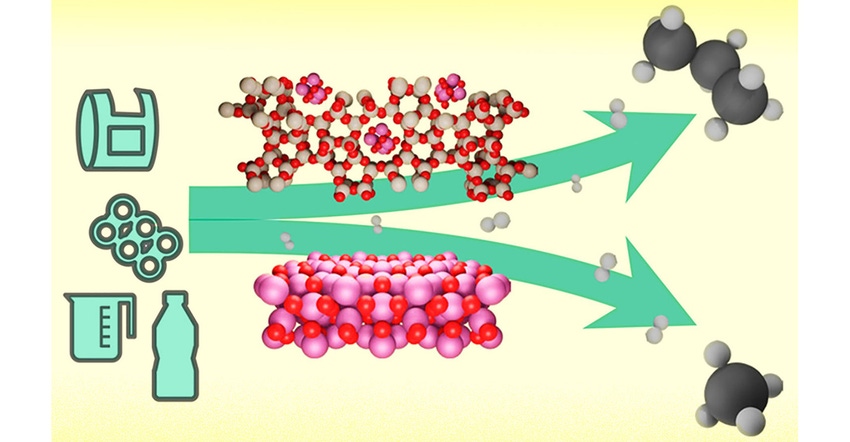

The article mixes up PET and PE and includes a drawing (above) that includes a water/soda bottle, which is made from PET, chemically very different from polyolefins and already valuably recycled. Not irrelevant, as it appeals to people who see lots of plastic bottles and think all plastics are harmful.

The drawing is also misleading as it shows the feed of a complex hydrocarbon which may derive from PE/PP but isn’t our familiar view of long chains. Also, the product is propylene, not propane. Propylene may be worth more than propane and doesn't need added hydrogens. The drawing also shows production of methane, a greenhouse gas that isn't wanted, especially in the air.

The article states that the economics to make propane and sell it are promising, but the authors give neither investment nor operating nor sales/price data. And there’s nothing on energy needs in kilowatt-hours, which may make the process less attractive to many environmental-minded people. You need to break a lot of those strong C-C bonds to break the polymer chain, a basic flaw in much advanced/chemical recycling except some pyrolysis.

Lastly, the article invokes the popular image of plastics in our bodies, ignoring the impossibility of digestion or circulation. Micro-plastic particles are far too big to penetrate the gut wall and then circulate through our network of capillaries. And how much matters, as I often say. Discarded fishnets may be harmful to aquatic creatures, but so is catching fish and eating them.

Yet, many people still want to believe that micro-plastics are inside us to support their need to resist science, which deprives them of the comfort of miracles. They are quick to label plastic as toxic because it is:

unnatural (but earthquakes, rattlesnakes, and viruses are natural);

chemical (but everything is chemical, including water, air, and us);

changeable (but so is weather and our bodies);

synthetic (but so are many medicines and foods);

corporate (but corporations can be creative, and volume and efficiency can keep prices down when responsibly regulated).

What we really fear is ourselves — humanipulation.

It isn't only the unscientific masses who think this way. Our own industry is doing what the public — our customers — wants when it talks about sustainability and circularity, and the politicians correctly see such myth-understanding as doing what the voters want.

Waste is a separate and opposite problem from pollution. Waste is losing good stuff, but pollution is the presence of bad stuff. Our plastics industry can and should reduce its waste. But don’t single out plastics as more wasteful than other materials, and remember that they reduce other waste — food, energy, water — and keep us healthy, as they don’t support bacteria (as wet paper does) and, thus, prevent sickness and help in the cures.

Plastics are relatively harmless but people want them to be bad? Yes, and now maybe you see why.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like