3D Printing Takes a Bite Out of Mosquito Research Barriers

3D-printed synthetic skin embedded with blood-filled channels combined with automated data processing eliminate the need for human volunteers and blood-sucking budgets to study mosquito behavior.

February 16, 2023

Studying the feeding behavior of mosquitoes, to test the effectiveness of repellents, for example, typically requires human volunteers or animal subjects. That takes a chunk out of lab budgets, and the data can take many hours to process. Researchers have found a better way — 3D-printed patches of synthetic skin, eliminating the need for live subjects, and automated collection and processing of data using inexpensive cameras and machine-learning software.

In addition to being a buzz kill at outdoor gatherings and often painful, mosquito bites can spread diseases like malaria, dengue, and yellow fever. Hence, the need to study the insects’ behavior. Rice University bioengineers have teamed up with tropical medicine experts from Tulane University to use technology to advance our understanding of these blood-sucking pests.

To create a substitute for skin, a team of scientists including Kevin Janson, a Rice bioengineering graduate student and lead co-author of a study documenting the research, and his PhD adviser Omid Veiseh, used bio-printing techniques that were pioneered in the lab of former Rice professor Jordan Miller. In 2019, his research led to a breakthrough in tissue engineering.

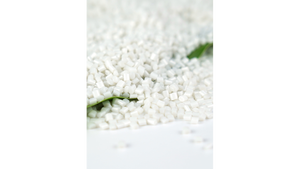

Hydrogel has blood-carrying channels

The synthetic skin is printed using a hydrogel with tiny channels through which blood flows. As many as six of the hydrogels can be placed in a transparent plastic box about the size of a volleyball. The chambers are surrounded with cameras that point at each blood-infused hydrogel patch. Mosquitos are placed in the chamber, and the cameras record how often the insects land at each location, how long they stay, whether or not they bite, how long they feed and so forth, explains an article on the Rice University News website.

The system was tested at the laboratory of Dawn Wesson, a mosquito expert and associate professor of tropical medicine at Tulane’s School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine.

In the proof-of-concept experiments featured in the study published in Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, Wesson, Janson, and co-authors used the system to examine the effectiveness of existing mosquito repellents made with either DEET or a plant-based repellent. Tests showed mosquitoes readily fed on hydrogels without any repellent and stayed away from hydrogel patches coated with either repellent. While DEET was slightly more effective, both tests showed each repellent deterred mosquitoes from feeding.

Technology makes testing more affordable for labs

Veiseh, the study’s corresponding author and an assistant professor of bioengineering in Rice’s George R. Brown School of Engineering, said the results suggest the system can be scaled up to test or discover new repellents and to study mosquito behavior more broadly. He said the system also could open the door for testing in labs that couldn’t previously afford it.

“It provides a consistent and controlled method of observation,” Veiseh said. “The hope is researchers will be able to use that to identify ways to prevent the spread of disease in the future.”

Wesson said her lab is already using the system to study viral transmission of dengue, and she plans to use it in future studies involving malaria parasites.

“We are using the system to examine virus transmission during blood feeding,” Wesson said. “We are interested both in how viruses get taken up by uninfected mosquitoes and how viruses get deposited, along with saliva, by infected mosquitoes.

“If we had a better understanding of the fine mechanics and proteins and other molecules that are involved, we might be able to develop some means of interfering in those processes,” she said.

This research was supported by the Robert J. Kleberg, Jr. and Helen C. Kleberg Foundation.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like