Discarded CDs Turned into Biosensors to Alleviate Waste

A non-toxic, inexpensive process upcycles the little-used music technology into a health-monitoring sensor.

August 16, 2022

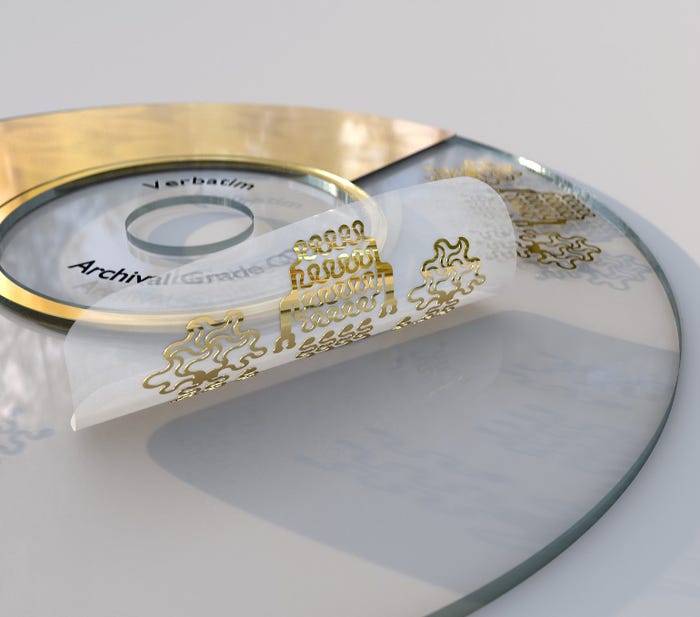

It wasn’t that long ago that compact discs (CDs) were the primary way people consumed music. However, since the advent of the digital age, this technology is rarely, if ever, used anymore, creating a scenario in which billions of discarded music CDs are filling up landfills and having a negative effect on the environment. Researchers at Binghamton University have found a potential solution to the problem by upcycling and repurposing CDs into flexible health sensors through a sustainable manufacturing method, they said.

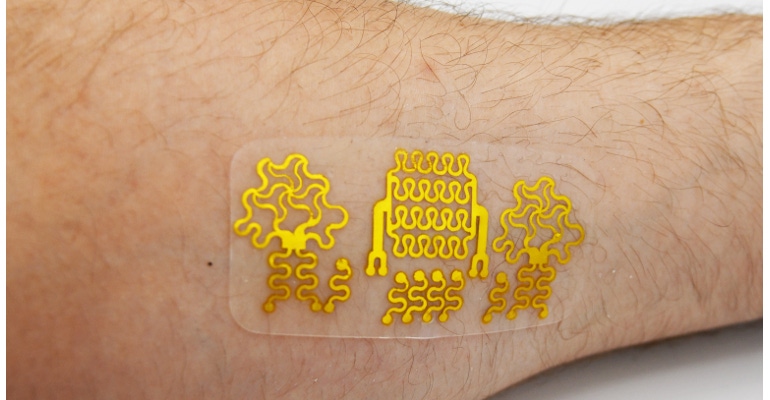

A team led by Binghamton Assistant Professor Ahyeon Koh in the university’s Department of Biomedical Engineering developed a way to separate a gold CD’s thin metallic layer from the rigid plastic to turn into a range of biosensors, they said. These sensors can monitor electrical activity in the heart and muscles as well as measure lactose, glucose, pH and oxygen levels.

Koh first had the idea to convert the CDs to sensors during her time as a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Illinois, where she pondered how to harvest the critical material from the disc to upcycle it into a sensing system, she said.

Koh later spoke to Binghamton PhD student Matthew Brown about her idea while he was researching his own dissertation, and he decided that this is something he wanted to pursue, giving new life to her idea, she said.

“I was so lucky to have Matt in the lab, because otherwise it would have stayed an idea from my postdoc research,” Koh said in an article for BingUNews. “Some of my postdoc colleagues remember me talking about this idea to them, and they’re so excited about it.”

Finding the Right Upcycle Method

It was not a direct path to finding an efficient way to upcycle the CDs, however, researchers said. Previous research on developing biosensors made from CDs created technology that was rigid and limited in terms of their applications, something upon which researchers wanted to improve.

The task then became finding a way to remove the metallic coating from the plastic beneath, which was done using a chemical process and adhesive tape, similar to how people remove dog hair from their clothing with a sticky roll of material, Koh said.

“We loosen the layer of metals from the CD and then pick up that metal layer with tape, so we just peel it off,” she explained.

Researchers then processed the resulting thin layer into a flexible material that could be reused to create the sensors. This was done using an off-the-shelf crafting machine called a Cricut cutter, which is typically used to cut designs from materials like paper, vinyl, card stock, and iron-on transfers.

The entire process—which is nontoxic, completed in 20 to 30 minutes, and costs about $1.50 per device—resulted in flexible sensors that could be stuck onto someone for monitoring through a connection to a smartphone app, researchers said. They envision that medical professionals or patients could get readings on people’s vital signs and track progress over time using the system.

Advancing Sensors Research

Binghamton Professor Gretchen Mahler and PhD students Melissa Mendoza and Louis Somma also contributed to the work, along with Assistant Professor Yeonsik Noh from the University of Massachusetts-Amherst. The team published a paper on their research in the journal Nature Communications.

Having completed his PhD, Brown will now take a position at a company that makes continuous glucose monitors, Dexcom. But he hopes to continue to improve the sensor technology to explore the use of silver-based CDs in a similar process.

“We also want to look at if we can utilize laser engraving rather than using the fabric-based cutter to improve the upcycling speed even further,” he said in a press statement.

From her position at Binghamton, Koh, too, hopes to further the work as well, potentially by creating a way to collect CDs from students on campus. She also wants to open up the design of the sensors to the community so the technology has a wider reach.

“We also could have more generalized step-by-step instructions on how to make them in a day, without any engineering skills,” she suggested. “Everybody can create those kinds of sensors for their users. We want these to become more accessible and affordable, and more easily distributed to the public.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like