Microbes to the rescue in marine plastic pollution?

"Epiplastic microbiota," says a new study from the University of Western Australia, are an important force affecting the fate of marine plastic pollution. PhD candidate Julia Reisser and colleagues have published an article in the international journal PLOS One, in which they describe an "epiplastic community" successfully living off the plastic debris floating around in the oceans of Australia.

June 23, 2014

"Epiplastic microbiota," says a new study from the University of Western Australia, are an important force affecting the fate of marine plastic pollution. PhD candidate Julia Reisser and colleagues have published an article in the international journal PLOS One, in which they describe an "epiplastic community" successfully living off the plastic debris floating around in the oceans of Australia. Remarkably, the researchers found that colonies of these tiny organisms were not only eating microscopic pieces of plastic debris, in some cases their weight was causing the plastic to sink to the bottom of the ocean, thus removing it from the surface of the ocean, where major environmental impacts can occur.

Millimeter-sized plastics, which are known as microplastics if smaller than 5 mm, are abundant in most marine surface waters. They originate from the disintegration of discarded plastic items and trash that end up in the marine environment. Up until now, however, little research has been directed at the organisms that attach themselves to and colonize these marine microplastics. This study was the first to document biological communities on plastic pieces from Australian waters.

Millimeter-sized plastics, which are known as microplastics if smaller than 5 mm, are abundant in most marine surface waters. They originate from the disintegration of discarded plastic items and trash that end up in the marine environment. Up until now, however, little research has been directed at the organisms that attach themselves to and colonize these marine microplastics. This study was the first to document biological communities on plastic pieces from Australian waters.

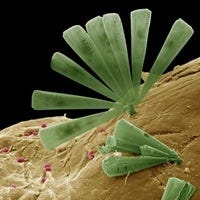

More than 1,000 images were taken while examining ocean plastics from Australia-wide sample collections using a scanning electron microscope at UWA's Centre for Microscopy, Characterisation and Analysis. The oceanographers observed a variety of plastic surface microtextures, including pits and grooves conforming to the shape of microorganisms, suggesting that biota may play an important role in plastic degradation. "These observations, along with detections of hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria genes on marine plastics and experiments demonstrating that marine bacteria can biodegrade, strongly suggest that plastic biodegradation is occurring at the sea surface," write the researchers. They surmise that this might also partially explain why the quantities of marine microplastics are not increasing as much as expected.

"Plastic biodegradation seems to happen at sea. I am excited about this because the 'plastic-eating' microbes could provide solutions for better waste disposal practices on land," Reisser said.

But she also said "epiplastic" organisms could also make ocean plastics more attractive as food source for "invertebrate grazers," with unknown consequences. "As plastic debris can contain harmful substances it remains unclear if such grazer-plastic relationships would have a positive or negative impact on the populations involved in this new type of food web," is how the article phrases it. Furthermore, species living on ocean plastic could disperse across oceans, potentially invading new habitats and impacting local ecosystems. This phenomenon has considerable ecological ramifications and deserves further research.

Reisser's PhD surveys were conducted aboard vessels of the Marine National Facility, Australian Institute of Marine Science, and Austral Fisheries. She is receiving an International Postgraduate Research Scholarship and a CSIRO Wealth from Oceans Top-Up Scholarship.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like