Environmental Impact of Single-Use Plastics Is Overstated, Say Scientists

The fixation on eliminating plastics distracts from less visible and often more damaging environmental impacts associated with energy use, manufacturing, and resource extraction, according to one researcher.

October 28, 2020

Could it possibly be that the scientific community is finally stepping up to reveal the real problems with plastic waste and, perhaps, helping consumers as well as plastic-haters to see the light? Phys.org has posted several articles in a series from the University of Michigan: “Mythbusting: Five common misperceptions surrounding the environmental impacts of single-use plastics.”

The first piece in the series, “Plastics, waste and recycling: It’s not just a packaging problem,” published on Aug. 25, 2020, pointed to a University of Michigan study showing that “two-thirds of the plastic put into use in the United States in 2017 was used for other purposes [than packaging], including electronics, furniture and home furnishings, building construction, automobiles, and various consumer products.”

While the study noted that plastic packaging “clearly warrants current efforts on reduction and coordinated material recovery and recycling,” plastics in packaging isn’t the only problem. Other sectors introduce unique challenges as well as opportunities to “shift away from the largely linear flow of plastics and toward a circular economy,” said the study.

The authors of the study created a detailed map of plastics flows from production through use and waste management and by type and market. Many durable goods that use large amounts of plastic do not get recycled. While previous estimates of recycled plastics, including one from the EPA, focused on solid plastic waste in municipal landfills, which comprises primarily containers and packaging, this new study includes plastic from construction and demolition waste and from automobile shredder residue.

It seems that plastic packaging gets a bad “rap” (don’t pardon the pun, please) because it’s the most visible. While I do see the errant plastic vehicle bumper laying on the side of the freeway periodically, most people do not equate vehicle bumpers with waste plastic. It’s the water bottle on the roadside or floating in the ocean that tends to get people’s attention, who then channel their ire at the plastics industry.

|

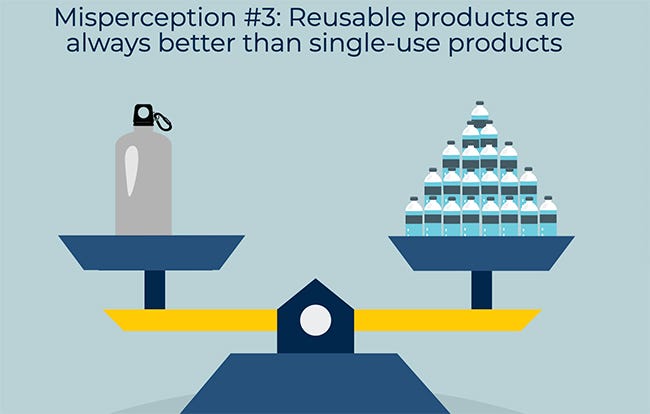

Image courtesy University of Michigan. |

Misperception #3 was published in Phys.org on Oct. 26, 2020: “Reusable products are always better than single-use products.” Go into any grocery store and look at the shelves filled with single-use plastic bottles and metal cans and it’s easy to conclude that there are too many single-use containers. But are these really the environmental problem that many claim? Shelie Miller, environmental engineer and University of Michigan Associate Professor at the School for Environment and Sustainability, notes that “in reality, most of the environmental impacts of many consumer products, including soft drinks, are tied to the products inside.

Mindful consumption trumps recycling

“Consumers tend to focus on the impact of the packaging, rather than the impact of the product itself,” said Miller, author of “Five misperceptions surrounding the environmental impacts of single-use plastic.” But mindful consumption that reduces the need for products and eliminates wastefulness is far more effective at reducing overall environmental impact than recycling, writes Miller. “Nevertheless, it is fundamentally easier for consumers to recycle the packaging of a product than to voluntarily reduce their demand for that product, which is likely one reason why recycling efforts are so popular.”

Miller also confirms for us, as numerous environmental scientists have previously, that the environmental impact of plastics is exaggerated. “Actually, plastic generally has lower overall environmental impacts than single-use glass or metal in most impact categories,” she said.

Another misperception is that reusable products are always better than single-use plastics. “Reusable products have lower environment impacts only when they are reused enough times to offset the materials and energy used to make them,” said Miller.

That brings to mind a comparison of plastic retail bags and paper sacks. In one study I read recently it was noted that you would have to reuse a paper bag at least seven times to offset the environmental impact of its production (trees, water resources, heavier transportation weight requiring more fossil fuel, etc.). Not many paper bags would hold up under that much usage.

Miller also notes another misperception: Recycling and composting should be the highest priority. “Truth be told,” she writes, “the environmental benefits associated with recycling and composting tend to be small when compared with efforts to reduce overall consumption.”

Miller also doesn’t hold out much hope that “zero waste” efforts to eliminate single-use plastics are of any real benefit. “The benefits of diverting waste from the landfill are small. Waste reduction and mindful consumption, including careful consideration of the types and quantities of products consumed, are far larger factors dictating the environmental impact of an event.”

She also notes that “efforts to reduce the use of single-use plastics and to increase recycling may distract from less visible and often more damaging environmental impacts associated with energy use, manufacturing, and resource extraction. We need to take a much more holistic view that considers larger environmental issues.”

Not only is this true of paper packaging — including the newest fad, the paper bottle — but of cotton retail bags, as well. They require extensive use of fossil fuels in farm equipment to prepare the cotton fields, plant the cotton, and distribute herbicides to keep weeds at bay and in aircraft that spray the defoliant on the cotton fields when the bolls are ready for picking. Fuel is also needed for equipment used to pick and bale the cotton and to send it to be processed into cloth.

Again, the general focus is on single-use products because they are visible.

“Although the use of single-use plastics has created a number of environmental problems that need to be addressed, there are also numerous upstream consequences of a consumer-oriented society that will not be eliminated, even if plastic waste is drastically reduced,” Miller said.

War against plastic a distraction from invisible pollution that is a greater threat

Live Science, an online scientific publication, reprinted an article on Oct. 26, 2020, from The Conversation, also an academic and scientific online publication: “The war against plastic is distracting us from pollution that cannot be seen.” This article also brings to light the fact that while we’re waging a war against plastic packaging, there are “greater threats to the environment.” The collaborators at The Conversation — experts with environmental science and engineering backgrounds, industry representatives, and policy wonks — have written a paper in the journal WIREs Water, highlighting concerns that “relatively easy action against plastic pollution can conveniently mask environmental apathy, and that people are being misled by alarmist headlines, emotive photographs, and greenwashing.”

We’ve written about all of these issues at PlasticsToday and noted how effective “emotive photographs” can be: Think a sea turtle with a plastic straw in its nostril. It hasn’t even been proven that it was a straw, yet it has led to a global ban on plastic straws. Greenwashing is another topic we have covered at PlasticsToday, including the rapid push toward bioplastics and biodegradable plastics.

Although there is widespread animosity toward plastics, “they are a group of materials that we cannot live without, and that we should not live without,” said the article from The Conversation. “We argue that plastics themselves are not the cause of the problem, and that failing to recognize this risks exacerbating much greater environmental and social catastrophes.”

The Conversation’s article notes that there are far more things polluting the environment than plastics, but most people are unaware of that fact. “Agriculture leads to nutrient over-enrichment and pesticide pollution. Electronics, vehicles, and buildings require a variety of toxic metals that leak into the environment at the end of their lives and are blown and washed from where they are mined. Medicines that are washed down drains and not completely metabolized by our bodies can also find their way into rivers and lakes.

“These lesser known realities of everyday consumption degrade the environment and are toxic to wildlife. As chemicals, rather than particles like plastic, these pollutants are also far more mobile than plastics and, in the case of toxic metals, more persistent,” said The Conversation article. “Plastic pollution provides a convenient distraction from these inconvenient truths.”

The article goes on to mention that many alternatives to plastic, such as cotton and wool, “recently have been found to dominate environmental samples” and may leach harmful chemicals such as dyes. Glass and aluminum alternatives to plastic bottles and containers, while promoted as solutions to the so-called plastic pollution problem, have their own problems and often “have greater carbon footprints than the plastics they replace.”

The Conversation article agrees with the University of Michigan study and concludes — rightly, in my book — that “the problem is the product, not the plastic. A desire for convenience, industries reliant on overconsumption not informed consumption, and a culture of policies for popularity not progressions, are all at the root of the plastic conversation. But the plastic pollution is just the bit you can see.”

It’s refreshing to see a number of scientific articles lately attempting to get people to reconsider how they think about plastics. The science is important! I’ll say it again: At the end of the day, it’s not a plastics problem, it’s a people problem.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like