By Design: There’s no such thing as too simple to fail

Often the “easy” projects are the ones that cause problems.I lost my first job after college in the recession of 1958. That traumatic experience gave me a permanent dread of recessions. I lived through the recessions of 1958, 1974-75, 1980-81, 1989-91, and 2003. I thought each was the end of the world. In every case the economy recovered and business was better than before. I expect the same thing to happen with this recession. Greed and globalization are more pervasive today. That may slow down the recovery, but the American system will prevail.

July 30, 2009

Often the “easy” projects are the ones that cause problems.

I lost my first job after college in the recession of 1958. That traumatic experience gave me a permanent dread of recessions. I lived through the recessions of 1958, 1974-75, 1980-81, 1989-91, and 2003. I thought each was the end of the world. In every case the economy recovered and business was better than before. I expect the same thing to happen with this recession. Greed and globalization are more pervasive today. That may slow down the recovery, but the American system will prevail.

|

I spent the next 10 years designing and developing healthcare products and pharmaceutical packaging at Abbott Laboratories. In 1968 I founded a company that provided product design, development, model making, and prototype molding services. One of my first customers was Walter Franks, a molder for several of the well-known cosmetic companies.

Recession-proof products

I didn’t know the significance of it at the time, but I went into business in three relatively recession-proof markets. Healthcare products continue to be developed during recessions. The cosmetics industry fights recession with new packaging, colors, fragrances, and promises. The third area was plastic packaging, which was and still is the largest single market for plastic materials. I have pursued these markets for more than 40 years and that kept the company going during recessions. What follows is one of these recession-proof products that got me into trouble.

The product came to me from Walter Franks. The purchase order called for a prototype mold and several hundred molded parts. These parts were to be used for market testing.

The project involved a hexagonal over-cap to be used on a purse-sized aerosol perfume bottle. The cosmetics company provided a beautiful rendering of the closure on a bottle, but without any details. The glass bottle was a rich reddish-brown color. The closure was to have a gold-colored, vacuum-metalized finish.

The first mistake

|

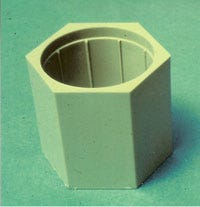

I was familiar with this project as a result of the sales and quoting activities. I knew this was a simple closure that did not require my personal attention. That should have been a tip-off, but I missed it. One of my project engineers designed the closure shown far left and followed it through tooling and sampling.

The outside of the closure had to be an extension of the hex-shaped glass bottle. The only place for the closure to attach to the bottle was the outside diameter of the metal aerosol valve ferrule crimped onto the neck of the bottle. The inside of the closure was round to accommodate the round aerosol valve. The diameter of the crimped valve ferrule varied from bottle to bottle. The vertical crush ribs on the inside of the closure were added to accommodate these variations.

The prototype mold was quoted as a simple single-cavity, top-center-gated, stripper-plate tool. The customer objected to a gate scar on the highly visible top surface of the closure. The mold design was changed to gate the part through the core pin. This produced an inside bottom center gate, leaving the outside of the closure without blemishes.

The second mistake

Sampling of the mold was uneventful. The closures made a secure fit on the bottle. There were slight vertical weldlines on each of the six flat sides of the closure, which was a surprise, as a top-center-gated part of this shape should not have weldlines. They were not bad, as weldlines go, and samples were sent to our customer for review and approval.

The third mistake

Walter Franks commented on the weldlines, but went ahead and metalized the parts. I learned something from that. Metalizing highlights any surface imperfections. I had to admit that the weldlines looked bad on those highly reflective flat surfaces.

Walter Franks was now late on delivery and made the mistake of submitting metalized parts to Helena Rubenstein, which assembled the closures onto perfume bottles. The alcohol in the perfume attacked the weldlines and the parts split.

At this point I was brought back into the project by being summoned to a Walter Franks damage control meeting. The molder had been embarrassed in front of an important customer, and my company was rightly blamed for the problem. I was instructed to lose the weldlines, mold acceptable parts, and be quick about it. I left the meeting with my tail between my legs.

I was ashamed to admit it during the meeting, but a glance at the parts told me what had produced the weldlines: The wall thickness at the corners of the hex was twice as thick as the walls at the center of the six flat sides.

As the melt entered the cavity, it first flowed across the top of the part. It then made a right-angle turn and flowed down the sidewalls of the closure. At that point the melt took the path of least resistance and flowed along the thicker corners of the part. As the cavity continued to fill, melt flowed from the corners and met melt flowing from other corners. When these melt flow fronts met, they created the unexpected weldlines (sequence represented in the third photo).

Eliminating the problem

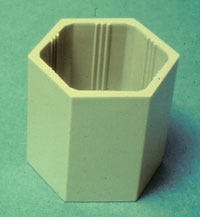

While considering ways to eliminate the thick corners, it was noted that the closure could fit the aerosol valve without being round. This observation resulted in the redesigned closure in the second photo. The round inside of the original design was changed to a hexagonal shape that duplicated the outside of the closure. This change minimized the increase in thickness on the corners. A fitment onto the aerosol valve was achieved by crush ribs on the straight walls between the corners.

The round prototype mold core pin was changed to a hexagonal shape. During the cavity filling process, the melt flowed uniformly along the sidewalls of the part. The melt no longer separated into individual flow fronts that reunited to create weldlines. The closure no longer had weldlines to be highlighted by metalizing or attacked by the alcohol in the perfume. The redesigned parts were approved. Multiple-cavity tooling was built and put into production without incident.

It is interesting to note that the redesigned closure with its uniform thickness used less material. The molding cycle time was reduced and there was no longer a tendency for sink marks at the thicker corners.

The fourth mistake

The moral of this story is that complex parts command our care and attention. Simple parts don’t solicit the same concern, but they should. It is a mistake to tell yourself that a project is too simple for your personal attention. It is often the simple parts that create unpleasant surprises.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like