Focus, eagerness for a challenge not strangers to this processor

Have the guts to take on tough projects: In large part because the company welcomes a challenge, injection molder Spang & Brands decided in 1982 to devote itself exclusively to the medical market, and it has not looked back since.

February 18, 2010

Have the guts to take on tough projects: In large part because the company welcomes a challenge, injection molder Spang & Brands decided in 1982 to devote itself exclusively to the medical market, and it has not looked back since.

That a project fits within the medical/pharmaceutical market is practically the only limit the processor sets on its projects. “We’ll mold as few as 5000 pieces and as many as 70-80 million,” according to Volkmar Rolli, quality control manager, who met with us. “We’ll mold whatever material is needed.” The current company evolved from Spang & Brands’ start as a shoe manufacturer, with plastics (soles) entering the picture in the 1950s. “We’re entering the dental market too, though we don’t yet have a commercial part,” adds Rolli.

|

The molder has 80 full-time employees and, at present, 20 part-timers. Its processing facility is equipped with 58 molding machines, 50 from Arburg, including its first electric press, acquired in 2004. In 2007 it acquired its first Fanuc electric machine, and since has bought another four from that manufacturer. There are three Class 100,000 cleanrooms, primarily for low-volume assembly, although four molding machines also are housed in the cleanrooms, and 15 automatic assembly units. Two of the molding machines are fitted with extra barrels to process multimaterial parts (Rolli: “They’re not yet running at capacity but are heading that way”). The presses not housed in cleanrooms are fitted with covers over the molding area, with hoses bringing clean air there. Moldmaking is handled in-house. The company has apprenticeship programs for moldmakers and for plastics processing technicians.

The company enjoys challenges—or, better to say that its owner, Friedrich Echterdiek, the third generation of his family to run the company, welcomes finding challenging projects for his team. One such project involved the molding of tubes for tracheotomy kits.

“These are tubes that really shouldn’t be moldable,” is how Rolli describes the work, showing us a curved tube that he correctly notes has no business being successfully ejected. Rolli won’t share how the company does actually eject the tubes, but he doesn’t deny that the mold for them has some moving parts. A thermoplastic elastomer is processed that includes an additive that reacts with a patient’s bodily fluids so no coating is required on the tube; often the coating can cause irritation or even an allergic reaction.

At €2500/kg, there is

little room for error

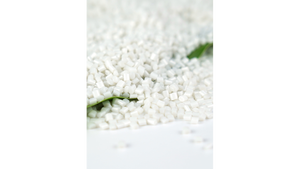

As is often the case, hard projects also are claimed from less-apt molders. One such project, an implant processed on an Arburg machine, is made from a material that costs €2500/kg, says Rolli. “The material isn’t just expensive, it’s tough to mold, too; we need 2500 bar to fill the tiny cavity,” he adds.

Spang & Brands took over the project from a molder that had a 70% scrap rate on the parts—and the scrap cannot be ground and reprocessed. “No one wanted this job, except the boss. He said we could do it...and said if we can do it, then we can take on any project. And he was right.”

Quality control during molding of these parts is assisted with the use of a camera fitted into the mold, along with mold pressure sensors supplied by Swiss firm Kistler. Rolli says his company exports about 500,000 of the parts annually to the OEM’s site in Puerto Rico. Each part has two tiny hooks; these are stapled into a patient’s skin to hold, for instance, a surgical net in place. After two years, the plastic parts biodegrade.

Although the medical market has attracted many new competitors, Rolli says so far his firm has not noticed any increase in the number of former automotive processors in medical. “What we do see is that the medical industry is going though a period of frequent mergers and acquisitions, and some of the large medical device companies have their own captive processing operations or have acquired them,” he says.

With competition getting tougher, Spang & Brands has raised the level of service it offers. For a mixing and dosing system for bone cement, used in orthopaedic surgery, the company molds 17 parts, purchases others such as hoses and springs, and hand-assembles the parts. These are then packed by the processor, barcoded, and shipped directly to hospitals, with the brand owner never seeing the finished kits. “It’s new for us—yes, it’s certainly a bit scary to take on so much responsibility. But it’s been a big success.” Taking on challenges, responsibility, and new technology seems to have proven a clear path to medical success at this processor. —Matt Defosse

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like