What Sustainable Solutions Make Sense for Plastics?

The tension between engineering and marketing is never more apparent than in sustainable packaging decisions.

April 17, 2024

An early Happy Earth Day to all! The good folks at this fine publication have kindly asked me to use this occasion to expound on the question asked above directed at plastic packaging.

Let’s start with the fact that the answer should be scientifically based. If you agree, the path is rather straightforward, don’t you think?

But hold on. What sciences are we talking about?

If you’re an engineer and primarily a left brained person, you’re going to think about and apply the natural sciences to your decision making: physics, chemistry, biology, and ecology.

However, if you’re a marketer and generally a right brained person, you’re probably going to think about and apply the social sciences to your thought processes: psychology, economics, anthropology, and sociology.

As a packaging engineer, the questions you would ask yourself are: “What are the key causes of global environmental degradation; and what can we do to improve our packaging to help mitigate them, ensuring that our planet will be sustainable for human beings over the long term?”

But as a consumer-packaged goods marketing professional, you’ll ask yourself very different questions: “What environmental issues relating to our products and packages do customers need us to solve to maintain or increase both our brands’ profitability and market share; and what are the returns on the different investment scenarios that we think can effectively deliver the solution(s)?”

What a conundrum! In fact, we’ve just hit the longstanding divide pitting the consumer perceptions to which marketing caters against the environmental reality where packaging design, science, and engineering must logically focus.

RICK LINGLE/CANVA

Consumers seem to only want one thing: Packaging that has been, or could be, recycled. Enter the marketers, with their desire to fill consumers’ psychological needs to feel good about the products they purchase, regardless of the actual benefits to the Planet.

Thus, we hear about ever new recycling processes that may or not be scalable, and packaging with only the theoretical possibility of being recyclable today, tomorrow, or even well into the future. And, while recyclability may alleviate consumer guilt and reduce some amount of litter, it frankly isn’t either efficient or effective enough to significantly reduce greenhouse gas generation. But that’s for another article…

Conversely, packaging engineers have always focused on material science, looking for ways to enhance packaging functionality while reducing the use of materials, energy, and associated environmental contaminants. Their mantra has been one of source reduction, which reduces greenhouse gas generation, but also increases the presence of post-use materials (alas, primarily plastics and microplastics) into our land, sea, and air.

As an aside, we’ve known for years that the true value of plastics lies in their high strength-to-weight ratio, thus significantly reducing material and energy usage, along with greenhouse gas generation.

How do we resolve what appears to be two competing sustainability philosophies, one of which is not readily understood or accepted by consumers but delivers many environmental advantages, while the other is well understood and accepted by consumers but delivers lesser advantages?

ROBERT LILIENFELD

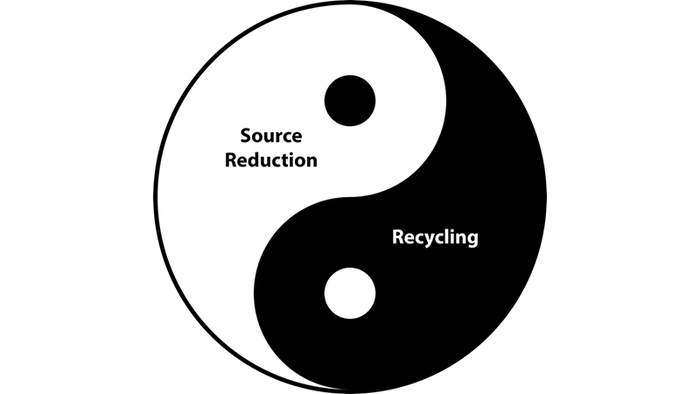

The Yin and Yang of sustainable balance.

The answer lies in the notion of balance. To optimize the sustainable value of packaging, we must stop thinking of source reduction and recycling as separate and competing entities, but rather as two parts of a waste management whole: The concept of Yin and Yang perfectly illustrates the idea of balance. As shown here, source reduction and recycling should be seen as two parts of one whole, which quite ironically, is best viewed as circular. Both exist simultaneously, equally, and harmoniously. In the area of source reduction’s greatest influence, recycling holds little sway. Conversely, the area of recycling dominance includes little prominence for source reduction.

Isn’t this the cold, hard reality that we’ve avoided explaining to the public? The value of flexible plastic containers and bags is their amazing ability to source reduce. This inherent benefit means that low-density polyethylene packaging significantly reduces greenhouse gas generation, but its light weight makes it hard to recycle and thus more easily leaked into the environment.

It also means that rigid PET, high-density polyethylene, and polypropylene containers are easier and more efficient to recycle, but their weight and reprocessing inefficiencies reduce their effectiveness as reducers of greenhouse gas generation.

You’ll note that this model also reconciles the differences between the natural and social sciences. Neither can stand alone. Both are critically needed if we are to…

A. First understand the scientific underpinnings of packaging design and development, and then...

B. Apply this knowledge by using proven marketing, communications, and sales techniques to educate and motivate materials suppliers, converters, CPGs, retailers, and consumers regarding their sustainable packaging decisions.

To answer the question posed in the title of this piece, the solutions lie within the spectrum created by the concept of balance. Each of you looking to develop more sustainable packaging must weigh the objective realities of science with the perceptual inclinations of human nature and judiciously apply these factors to your business. Thus, to be successful, you must use both sides of your organization’s collective brains.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like