NPE's Origin Story: Promoting and Defending Plastics

In 1946, the Society of the Plastics Industry (now the Plastics Industry Association) put on the first National Plastics Exposition in New York. “Nothing can stop plastics,” declared then SPI President Ronald Kinnear as he opened the show by cutting through a Vinylite film sealing the entrance.

April 5, 2024

Editor's note: Longtime PlasticsToday columnist Clare Goldsberry wrote this article in 2018. It has since been updated. Clare retired in 2021.

Can you believe that at one time plastic was too fantastic for its own good? It seems that so much effort went into promoting plastic as the “material of a thousand uses” that expectations were running high that it would soon become a plastic world. Numerous articles in the popular press trumpeted plastics as the answer to everything. The efforts to promote this new material in the 1930s had created a monster by the end of the war. The New York Times even ran a long feature in 1943 that portrayed “life in a plastic world,” as recounted in American Plastic: A Cultural History by Jeffrey Meikle (Rutgers University Press, 1995).

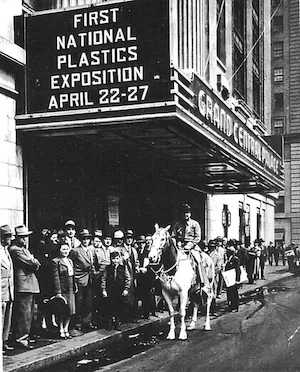

If you can make it there . . . the first NPE in New York in 1946. Image courtesy of PLASTICS.

William T. Cruse, who took over the editorship of Modern Plastics [the precursor to PlasticsToday] in 1940, was also a “courtesy” member of the Society of the Plastics Industry (SPI). When “SPI’s executive secretary became ill in October 1941, the board asked Breskin [the owner of Modern Plastics] to release Cruse” from the publication so he could fill the SPI vacancy. The hype of plastic as the material that can be and do anything concerned Cruse, who “within a week” of the Times article began an effort to “neutralize plastic utopianism,” writes Meikle. Cruse complained of "too many Sunday supplement features portraying plastic as a ‘miracle whip’ material with which anything can be done." That’s when a “deglamorization” program began to reduce the expectations of plastic.

The birth of a national plastics exposition

About that same time, SPI was planning a national plastics exposition to try to rein in the plastics enthusiasm of consumers, who by 1946 were discovering that plastic products could be really great or just plain junk that broke easily. In 1946, SPI put on the first National Plastics Exposition in New York. “Nothing can stop plastics,” declared [SPI] President Ronald Kinnear as he opened the show by cutting through a Vinylite film sealing the entrance,” writes Meikle.

That show had 200 displays and wecomed 20,000 attendees on the first day. Meikle noted that attendance would have been much higher except that fire regulations forced repeated closing of the doors. And that was just industry people! “Three days later, when the general public was first admitted, people lined up four abreast for several blocks” to get into NPE, “hungry for something new . . . evidently, plastics are the answer," commented one show visitor. Another said, “the public are certainly steamed up on plastics.”

According to the accounts in Meikle’s book, the exhibitors were as fired up over plastics as the general public. One exhibitor “pronounced the exhibition ‘the first show where we really got our money’s worth, because customers were showing a terrific interest . . . the only question is when can you deliver?’”

A galvanizing event for industry

From those humble but very exciting beginnings, a plastics trade show culture was born. While NPE may have begun with the goal of “deglamorizing” plastic and educating people that it’s only a great material if it’s used for the right application, it became a galvanizing event for industry professionals looking for the next big plastics processing technology and the next profitable application that would wow consumers.

A particularly notable NPE date was Nov. 22, 1963, the day of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. John C. Reib, the founder of auxiliary equipment Conair, mentions in his history book, The Making of Conair, that “people simply left the show, and we exhibitors started tearing down our booths.”

In later years, NPE moved to Chicago and was held in November — aah, Chicago in November! By the time NPE rolled around in 1982, Conair had a backlog of over $3.3 million and $5.5 million in inventory. Conair had added people and went to NPE with a “large and expensive” showing, an “abundant finished goods inventory, plus $600,000 worth of equipment.” Reib anticipated selling a lot of equipment at NPE that year, as every NPE Conair had been to resulted in a “shot in the arm immediately afterward, often bringing in greatly increased business for the next six months.”

However, the recession that had begun in 1982 was in full swing by 1983 and, as Reib noted, it “had finally caught up with the auxiliary equipment business.” In spite of the effort, sales dropped in 1983.

From plastic tiles to Folgers coffee can lids

NPE was the place to go to find the latest and greatest technology in plastic processing. Landis Plastics, a family-owned company that was fortunate enough to get into injection molding in the early 1950s, fell into the business of molding plastic wall tiles, which were all the rage at that time. They came in a variety of colors and were cheaper to make and install — because they used adhesives — than ceramic wall tiles, which required layers of cement.

As ceramic wall tiles from Italy and Japan began to enter the market, the cost of tiles went down, as did installation costs since these tiles could be installed using adhesive like the plastic wall tiles. That competition eroded Landis Plastics’ market share, so the company began looking for something else to make.

Being experts at molding thin, flat wall tiles, Landis jumped at the chance to mold thin, flat four-inch round coffee can lids for Folgers. In 1962, Landis Plastics began molding coffee can lids using eight-cavity molds and running them in the company’s 400-ton presses, achieving a 12-second cycle.

Landis got a break when the reciprocating screw was developed, which made molding faster and easier. At the 1964 NPE, Henry Landis and his son Richard saw their “first reciprocating screw retrofit for injection molding machines using the older plunger technology," explained Richard (Dick) Landis in his family history book, The History of Landis Plastics Inc. “It was being offered by the Sterling Extruder Co., so we bought one and retrofitted one of our four-hundred-ton molding presses. It made a big improvement. The melt consistency was so much better that we could run even faster cycles.”

It was also at the 1964 NPE that Husky Corp. out of Canada introduced a “new molding machine with 100-ton clamping force that was running a four-cavity mold that could produce plastic coffee can lids at the incredible speed of a four-second cycle, which was revolutionary to say the least,” said Dick Landis in his history. “When I saw these new machines running at the Chicago show in 1964, I immediately ordered four of them on the spot."

Each new “machine could mold lids at the rate of 900 shots per hour on a four-second cycle in a four-cavity mold,” Landis added. “With the smaller 100-ton machines in place, we could produce 50% more lids per hour.”

Truly, NPE from its earliest days was the trade show to find all the latest technology in machinery and equipment, including molds. It was the place to get new business, discover new ideas for manufacturing, make new business acquaintances, and form lasting friendships. And it still is.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like