Sponsored By

3D Printing

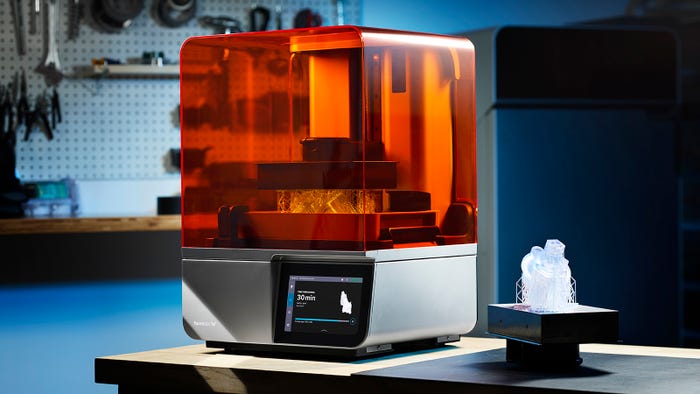

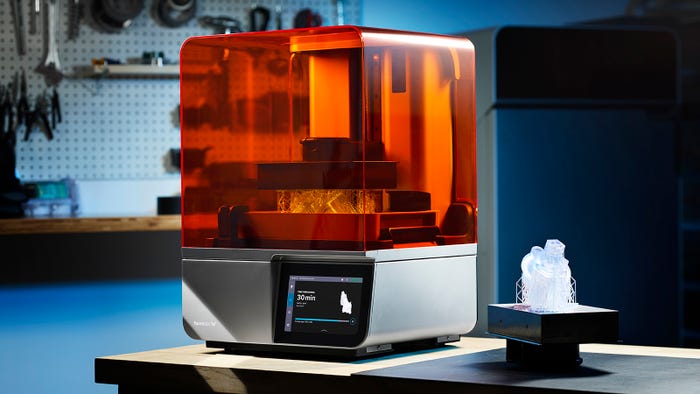

Formlabs' Form 4 3D printer

3D Printing

Formlabs Releases Fastest 3D Printer YetFormlabs Releases Fastest 3D Printer Yet

The Form 4 can achieve vertical print speeds of 100 mm per hour and outpace injection molding, according to the company.

Sign up for the PlasticsToday NewsFeed newsletter.