Sponsored By

Medical

quality dial

Medical

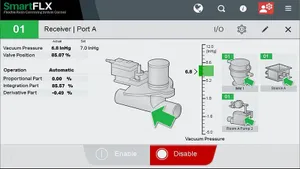

How to Optimize Your Medical Injection Molding ProcessHow to Optimize Your Medical Injection Molding Process

To consistently mold components that meet quality control specs and reduce development hours for customers, follow these steps.

Sign up for the PlasticsToday NewsFeed newsletter.