Sponsored By

News

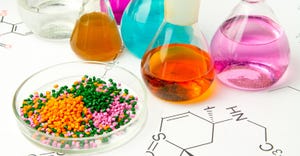

plastic resin

Resin Pricing

Resin Price Report: Spot PE Flat, PP Drops Two More CentsResin Price Report: Spot PE Flat, PP Drops Two More Cents

Buyers eye significant decrease in PP contract prices.

byStaff

Sign up for the PlasticsToday NewsFeed newsletter.